This is a post about the difference between experiencing a story and remembering it later, a distinction that we pay too little attention to in the media world. I’ll talk about theater, movies, TV, Superman, Thor and Shakespeare, and there will be spoilers… lots of ’em about the “Smallville” series finale, but I’ll be careful when it comes to “Thor.”

Those readers who have been following this blog or my other work at all will know that I’m a lifelong superhero geek, and over this weekend I hit a rare caped trifecta, watching the “Smallville” series finale, taking in the new “Thor” movie and receiving a big box of comic books from the shop in Los Angeles where I’ve been going since 1998. I’m chewing my way through the comics, loved Thor (a bit more on this at the end) and have had a weird response to the Smallville finale where the farther I get from it the less I like it.

Although I got bored with the Clark/Lana/Lex triangle a few years ago and skipped a half season, I’ve watched Smallville for 10 years through the births of my two children, big career changes and a move from Los Angeles to Portland, Oregon. The entire series has been a build up to the moment when Clark Kent puts on the blue costume and red cape and flies off to greet the world as Superman. I’ve spent a decade on this hero’s journey.

So why, in the much-advertised and long-awaited series finale did they deny us the money shot? Yes, we had Clark holding the costume, flying to the big battle while holding the costume, and then we had him, wearing the union suit, but in close up gazing lovingly through the round window of an airplane at Lois. Yes, we had a blue blur flying through the sky towards battle, and yes we had him – seven years later — (I did mention the spoilers, right?) running across the Daily Planet rooftop pulling open his shirt to reveal the big red S to show us that Clark now fully inhabited the Superman role.

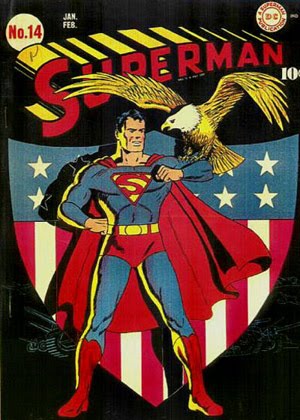

But we didn’t have this:

or this:

or this:

Why not? At one point I thought, maybe Tom Welling got fat– the way William Shatner plumped up during every season of the original “Star Trek” series (they only took his shirt off during the early episodes each season), but a quick tour through Google Images suggests that this isn’t the case.

It’s a huge failure on the part of the series, one that got me mulling over the flaws in the finale with a microscope… and that’s usually a bad sign. Days later, I realized that in addition to the lack of a money shot we also never heard the word “Superman” as a name, although we did have a Nietzschean moment where a character referred to a superman in flashback.

The worst series finale in TV history was “Quantum Leap,” where in a bump shot at the end we learned that Sam Beckett never returned home, even though the entire series was predicated on that return. When I saw that I lurched forward clutching my stomach like I’d been stabbed. Smallville, in contrast, couldn’t resolve this season on its own terms, spending most of the two hours on the soap opera and only a few minutes on the heroics.

The show runners got distracted by a bunch of characters to whom the audience had said goodbye years ago, most particularly Michael Rosenbaum’s Lex Luthor and John Schneider’s Jonathan Kent. Annette O’Toole’s Martha Kent made an appearance as well, but since her character hadn’t died a few seasons ago that made sense. Why the team didn’t bring back Kristen Kreuk’s Lana Lang (not that I wanted this) alongside everybody else has, I presume, more to do with Kreuk’s availability than anything else.

Yes, the mythology states that Superman will battle Lex Luthor forever, but we didn’t need to spend 10 minutes with Lex and Clark in conversation only to have Lex’s memory wiped in the final moments of the episode. Yes, the memory of Clark’s human father guides him, but we didn’t need to have the ghost of Jonathan Kent literally hand Clark the super suit. Ghosts are not a key part of the Superman mythos.

Nor did we need to kill off Lionel Luthor (who oddly turned into Gollum between his last appearance and the finale) and Tess Mercer just because they have no place in the comic book mythology. One of the great strengths of Smallville was the tension between the comic book mythology and its own—the series stopped being consistent with the Superboy/Superman origin story in the pilot, so why care so much in the finale?

In the finale we got too much of the man and not nearly enough of the super, but that has always been the case with the series. The problem was that the emotional drama of the tenth season was abandoned in favor of the Clark-growing-up arc that the audience finished years ago.

However, when I watched the finale on Friday night I rather enjoyed it. The eventful-ness of watching it on that night, carving out time after the kids were asleep and my wife was doing other things upstairs, watching it nearly in real time (I got a late start but caught up via DVR), these things swept me up and gave me that special momentum of real-time experience… the tide that carries us through experience.

The only thing I noticed in the moment was the lack of the costumed money shot, and my dissatisfaction with that gap is what kept me thinking about the finale, probing it like a tongue searching for a missing tooth. Then, to mix metaphors, the entire episode unraveled.

This phenomenon where time reduces satisfaction is well known in theater and makes a certain amount of common sense. When we are in the middle of things, particularly things that possess a great deal of eventness, we are surfing a wave of experience rather than mulling it over. The critic Bernard Beckerman expressed it this way in his 1979 book “Dynamics of Drama:”

The memorial experience is not distinct from the theatrical but merely a continuation beyond direct contact with the presentation. The form of action induces the theatrical experience directly but has an indirect effect upon the memorial experience. When unable to return to the same artistic work, the playgoer must either avail himself of a facsimile, such as a second performance of the same production, or be content to recall the initial experience. Once removed from his fellow spectators, he gains a new perspective of the work. Responses elicited in performance may seem alien in retrospect. The process of rumination alters the work (157).

Rumination is key to the superhero genre because after seventy plus years of stories about these characters they are saturated with inescapable foreknowledge. Do a search on famous fictional characters and both Superman and Batman show up early.

Even people who don’t know much about superheroes – my wife, for example, before our son joined me in the cape-o-philiac club – approach the genre knowing that the stories are embedded in a network of earlier versions of the tales and will be followed by later versions. Deeply satisfying stories within these contexts are aware of all their predecessors and heirs. J.J. Abrams’ reboot of the “Star Trek” franchise, for example, was brilliant in its deft balancing of the old and new versions of the universe.

And this brings me to “Thor,” which managed to weave into its two-hour span allusions to the 1960s “Thor” comic books, to King Lear, the Empire Strikes Back, the Lord of the Rings, the Lion in Winter and embedded itself neatly into the other Marvel Comics movies of the last few and next few years. This isn’t transmedia in Henry Jenkins‘s sense so much as a deeply allusive network of references and parallels that increases the satisfaction of movie going for the experienced viewer and gives her or him a qualitatively different evening than the newcomer to the genre.

I won’t perpetrate big spoilers for “Thor” because the movie is so worth seeing on the big screen in a top-notch theater with stadium seating. Visually stunning, charmingly acted and with an immense sense of scope, the combination of director Kenneth Branagh channeling his own Shakespearean movies (“Henry V,” “Hamlet,” “Much Ado About Nothing”) and story architect J. Michael Straczynski (who redefined the modern science fiction epic with “Babylon 5” and has spent the last couple years on Superman and Wonder Woman in comics) means that this movie understands and embraces epic.

“Thor” is a thrill ride (plenty of money shots with this one), and as my wife and I talked over the movie at dinner afterwards we found some things to pick apart (Natalie Portman joining Elizabeth Shue in “The Saint” in the ranks of brainy-sexy-unbelievable astro-physicists… although Portman is more convincing) but nothing that caused the experience to collapse in retroactive dissatisfaction.

Instead, we talked about how Loki echoes Edmund in King Lear, how this film links up with “The Incredible Hulk,” the “Iron Man” movies and the forthcoming “Captain America” and “Avengers” movies, and how Chris Hemsworth’s body is possibly the movie’s single-greatest special effect (as was that of Megan Fox in the first “Transformers” film).

Rumination, in the case of Thor, deepened engagement with both the story and the performance of the story, with the structure of the narrative and the way that the execution and casting (e.g., Anthony Hopkins as a Lear-like Odin) linked that performance to other stories.

Culturally, we tend to suffer from what I think of as the tyranny of the object when it comes to stories. We evaluate the thing itself and not the context in which we experience that thing. Our ability to buy just one song on iTunes means that we don’t think as much about an album, and the birth of new one-off journalism at Byliner (and see my previous post about Fortune) means that we don’t think about publications in the same gestalt way that we used to.

Both Smallville and Thor, though, are deeply contextual in their meaning-making and in the experiences of that meaning. Smallville is the end of the beginning of the Superman story. Thor is the start of that hero’s journey on earth and in the middle of the current Marvel movie epic.

The growth of digital media and distribution has eroded the easy context that came with analog media the way “Cheers” came after “The Cosby Show” to create NBC’s anchor Thursday night.

I believe that in the next few years we will pay more attention to context, and that in doing so we’ll also be more aware of the gap between the memorial experience and the in-the-moment experience of storytelling.

Good storytellers deliver on the in-the-moment experience. Great storytellers do that and also think about memorial rumination.

The take-away? Go see “Thor” while it’s still in the theaters.

Leave a Reply