I Pac-Man chomp my way through many articles each week, digesting most with a tiny burp and leaving them to the brass-knuckled mercies of memory. Yet two recent pieces have stuck with me: Matt Richtel’s October 10th piece in the New York Times, “In California, Electric Cars Outpace Plugs, and Sparks Fly” and Roberto A. Ferdman’s October 5th piece in the Washington Post, “How Coca-Cola has tricked everyone into drinking so much of it.”

Both articles deserve close reading, but in the interests of your time, dear reader, the quick summaries are 1) in California there are now orders of magnitude more electric cars than there are charging stations, which is provoking people to behave selfishly when they need to power up their cars, and 2) an interview with the ironically-named Marion Nestle (author of a book called “Soda Politics”) charts the “valiant and deplorable” lengths to which Coca-Cola has gone to habituate people to drinking evermore of its unhealthy product over many decades and compares the company’s efforts to those of Big Tobacco.

The collision of these two articles in my mind led me to a mild, week-long experiment, which is that I don’t check Facebook or email until after 10:00am each day. This piece is my attempt to unpack the “how the heck did I get to there from that?” of this experiment.

On the electric car dilemma, this is a crystalline example of how technology and behavior evolve in a complex dance: Darwin’s finches got nothing on Tesla, Leaf and Volt. Since electric cars are getting on the road at a slower pace than people sign up for yet another social media service, we can get a clear look at how behavior changes over a longer period of time: oversupply of electric cars plus undersupply of charging stations equals conflict.

<Digression> Before I go any further, confession time: if there were a support group called Facebook Anonymous for people who can’t stop checking Facebook I probably wouldn’t join because I’d be too busy checking Facebook.

I love Facebook. The problem is that I love Facebook more than Facebook loves me.

I neither want to dignify my lack of social media self-discipline with the word “addiction” nor trivialize the piercing challenges addicts have with alcohol and drugs, so let me simply say that I am on Facebook (oy it’s a lot), Twitter (at least daily, way more at conferences), Google+ (yup, I’m the one) and LinkedIn (do you like me? do you like me?) too much for my own comfort and productivity when I take time out to think about it.

The corollary behavior pattern is my over-involvement with email, which feels less like addiction and more like a punishment from God, but that’s probably just because email has been around longer and has therefore normalized itself in my sense of how the world works (see the Douglas Adams bit towards the end of this piece for more on how that works). </Digression>

Both articles are examples of The Problem with More.

We want more electric cars on the road, but we didn’t think it through and now we have people arguing about who gets what access to which charging station. It hasn’t gotten to the fight-fights-and-riots point yet, but I inferred a new form of pre-road rage is coming to California, from whence so many other technological innovations of dubious merit hail.

Coca-Cola’s profitability depends on getting more people to drink more of its products every year, and now, Marion Nestle says, a conservative estimate is that 50% of the US population drinks more than one can of soda per day, with many of those folks drinking much more— four cans plus. Coca-Cola denies any link between its product and an obesity epidemic.

More isn’t the opposite of less: it’s the opposite of enough.

We humans, Americans particularly, have trouble with enough. We want to earn more, go to the gym or spin class more, read more, spend more time on our hobbies, see our friends and families more, parent our children more, finish that project in the garage, be better about keeping up with the news of the world, bake bread from scratch, make our own clothes and brew our own beer. We also want to do better at the office, get that promotion, give that conference paper, go to that networking event and turn every meeting and interaction into a miracle of productivity that leaves our colleagues breathless with gratitude because now they can go back to playing with their iPhones.

This is where the myth of multitasking comes from.

Corporations have an even harder time — way harder — with enough. Public companies need more, lots more, to satisfy investors. Companies that are OK with enough get trivialized as “lifestyle businesses.”

We humans want more, so we squeeze more stuff in — both new stuff and more of the old stuff; corporations need us to squeeze more stuff in — preferably their stuff — in order to make the Street happy.

When corporations like Coca-Cola run up against limits in their customer base — that is, 50% of Americans do not drink soda — they need to get their existing customers, the other 50%, to drink more soda even though it’s unhealthy. Faced with this question, soft drink companies dodge either by focusing on how people don’t exercise enough or on how they have other products (diet soda, water) that aren’t as bad for people— this is a “guns don’t kill people, bullets do” argument.

It’s when we come to the issue of satisfaction that things get murky. If you know a little Latin, then you’ll already know that the word “satisfaction” literally means “to be made enough” from the combination of satis and facere.

Our workaday understanding of satisfaction is the “Ahhhh” of the first gulp of an icy Coke on a blistering summer day when you’ve just finished doing something sweaty. This is a transfixing moment: time stops. You enter what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls a flow state where your attention is 100% focused. For that one moment you need nothing else: you have been made enough.

Coca-Cola has built its formidable brand upon the rock of moments like this one. Just think about its current slogan: “Open Happiness.”

The problem is that there aren’t enough transfixing moments for Coca-Cola to be profitable, so the company sells satisfaction but then delivers routine, it promises magic but provides habit bordering on addiction. What psychologists call a Hedonic Set Point tells us that the second or third or fourth or fifth can of Coke can’t possibly create a moment like the first, but once you’re in the habit of associating thirst with Coke (rather than, say, water), you’re unlikely to stop.

Which brings me back to Facebook. When we dive or dip into Facebook the potential for magic always exists: the old friend’s new baby, the new friend’s witty comparison, the frisson when you realize that two people whom you know also know each other. But more often than not it’s click-bait, bad jokes or that day’s lunch pic by the perennial over-poster.

I have 1,528 connections on Facebook. I’m an overachiever since the average number, last I heard, was 140 (close to Dunbar’s number), but even though I have 10X the usual number of connections Facebook needs me to add even more in order to increase the number of interactions happening within its user base, so it can sell more advertisements.

As with Coke, more Facebook “friends” does not mean that I’m going to find my experience with Facebook more satisfying— it just means that there will be more of it. There are enough magical Facebook moments to keep people coming back, but paradoxically the more you come back the less often you’ll find that magical moment because Facebook has become routine.

<Digression> There’s another Facebook Problem with More, which is that Facebook presumes that any interaction I have with any person is an indelible mark of my interest in that person’s actions. If my friend Tim posts a cute picture of his dog, and if I make the mistake of interacting with that picture (a like, a comment), then the all-seeing Facebook algorithm concludes that I want to see more stuff from Tim.

But what if I’ve scratched my Tim itch? What if I have satisfied my craving for information about Tim for the next few months and no longer feel the need to see his dog posts? This never occurs to Facebook, which means that I then have to dive into the settings on one of Tim’s posts to turn down the gain or stop following him altogether, which is a homework assignment for I class I never decided to take. </Digression>

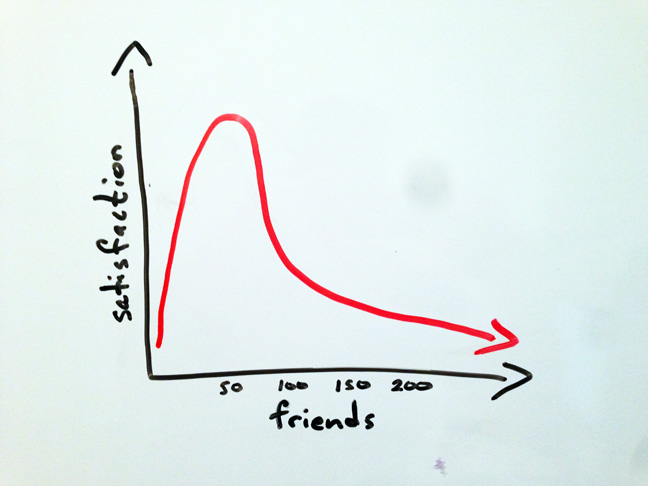

I’m confident that the satisfaction shape of having a lot of Facebook friends looks like this:

So the more friends you have the less satisfaction you’ll feel, and you’ll work harder to get those moments of satisfaction… which benefits Facebook on the surface because it generates more advertising inventory for them but at a plummeting quality.

Since I’m polite, I don’t want to unfriend a bunch of people on Facebook. And since Facebook’s filters suck ass — I can’t intuitively say, “more from THOSE 150 people, please” — the only thing I can do is limit the time I spend on Facebook in the hope that by making it less a chronic part of my day I’ll be able to notice more when the magic moments occur, and incidentally I’ll have more time to focus on my new bread-making hobby.

Hence this week’s experiment.

A closing irony: In addition to publishing this on my blog and on Medium, I’ll also post a link on Facebook and Twitter.

Leave a Reply