The difference between stories and real life is that stories make sense.

We humans love stories. We love to tell stories, and we love to consume stories even more. “Tell me a story!” little children command. Whether our stories are sweeping novels like Anna Karenina, a sweeping collection of TV series like more than a half century of Star Trek, a podcast, a puzzle, a comic book, a video game, the top story in your local newspaper, a joke, a fortune cookie, a tweet, a recipe, or a newsletter like this one, we live inside a never-ending series of stories.

Why?

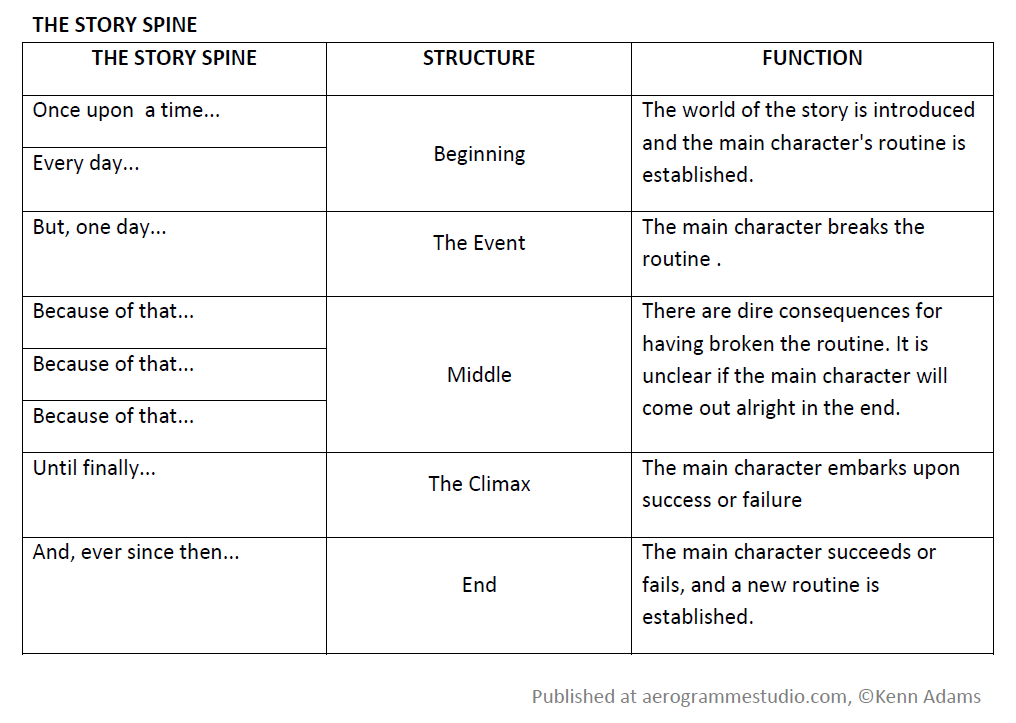

Stories comfort us because they exist in alternate worlds where things make sense. The playwright Kenn Adams created a remarkable tool called a “story spine” that pares all stories down to a universal structure:

I just glanced at my Twitter feed, and even with those micro-narratives you can infer a story spine in the background of a tweet.

The most important word in the story spine is “because.” One thing inevitably, inexorably leads to another. Things identifiably cause other things. At the end of a story we look back in comfort because in stories things are always heading to a place. Then, when we get to that place, we’re not only happy to see that particular place but we’re also happy that there are places at all.

Life isn’t like that.

Moment to moment, we don’t know what genre we’re inhabiting. Comedy can transmogrify into tragedy without warning. Or a light comedy (catch up coffee with a pal you haven’t seen for a while) can veer into an intense medical drama (you find out your friend has stage three cancer).

Shit happens.

All the time.

And we don’t live inside just one story. Erving Goffman, the great Twentieth Century sociologist, talked about different frames for different identities that we shuffle through like playing cards. Different narratives pull us in different directions. We become different people in response to the different stories we encounter. We have to code shift among different identities improvisationally in real time.

This was never more true than during lockdown when we got to see everybody’s stories poured into one crazy container—our homes via Zoom. One of my colleagues, John, had a suicidal 14 month old who never met a bookcase he wouldn’t climb or an electric socket he wouldn’t try to French kiss. John would leap offscreen out of his professional identity into his Dad identity, grab his son from the latest daredevil maneuver, and come back to his desk and back into his professional self with the boy squirming on his lap, alive and visibly plotting his next misadventure.

Is it any wonder we love stories? They’re comforting. Ever story has a beginning, middle, and an end. A while after you’ve reached the end, after that narrative has settled in your mind, it can be hard to imagine a different ending. The end that you reached seems like it was always the end that you were going to reach. It seems like it was destiny.

That’s never true in real life, and frequently it isn’t even true in fiction. The first pass a storyteller takes at an ending can change (just ask any focus group). Even after a story has been told, the ending can change. One of the reasons I like time travel stories (Back to the Future, Groundhog Day, About Time) is that they make us see that things could have gone another way.

In England in the early 1660s, after the Restoration of the monarchy and after theaters re-opened, a playwright named James Howard re-wrote Shakespeare’s Romeo and Julietas a tragic-comedy:

He [preserved] Romeo and Juliet alive; so that when the Tragedy was Revived again, ’twas played alternately, Tragical one day, and Tragicomical another, for several days together.*

Shakespeare’s version was already barely a tragedy: if Romeo had waited to drink the poison for just a minute things would have turned out differently (the 1996 Baz Lurhman movie with Claire Danes and Leonardo DiCaprio makes this excruciatingly clear). For a theater to play the “whoops!” version alternately with the “hooray!” version is an exercise in might-have-been awareness that I’d love to see at a theater festival today.

Why am I saying all this?

When life stops making sense, it can be because something that we thought was settled turns out not to be. A story that we thought was closed (“until finally”) opens back up and shifts onto new ground, into a new genre.

But that first ending was never meant to be. Nothing is ever meant to be. People chose that ending, created it. Other people changed it. It can be changed again.

“And they lived happily ever after” is bullshit outside of fairy tales. In real life, you have to choose and keep choosing.

* The quote is from a remarkable 1708 book by John Downes called Roscius Anglicanus, or an Historical Review of the Stage.

Leave a Reply