Note: I’m keynoting about wearables at the Brand Innovators Fashion Week event on Friday, February 14, 2014. The kind folks at Brand Innovators have published this piece as a white paper. You can learn more about the event and download the white paper here.

People talk about wearable computers in one lumpy category, but doing this erases a key difference between two overlapping — and often opposing — orientations of wearables: the display of old information and the creation of new information.

These orientations have a lot to do with time and whether at a given moment we prioritize present or future.

Being thoughtful about these two orientations can help people use wearables in productive ways that improve their lives, and doing so can also help people seize special moments. On the flip side, wearables can also add new layers of distraction to our already information-overloaded lives.

When it comes to industry — from media to health and wellness to CPG and beyond — understanding the differences between display and creation can help companies determine the right strategies for using wearables to help build businesses through analytics, advertising and partnership.

Display: here I’m talking about wearable computers that take information coming in from the world and stick it onto new spots on your body. This is translation in the literal, Latin-root sense of trans locare “to carry across.”

Google Glass perches on a user’s face: the device is a prominent prism in the upper right corner of a user’s glasses, which is a spot nobody paid much attention to before.

Although it has received a ton of press and even a witty new term — “Glasshole” — for people who wear it all the time, Google Glass isn’t the world-changing iPhone of HUD (“heads up display” or “on your face” information), it’s the Apple Newton.

There are other versions of HUD, including an interesting contact lenses plus glasses approach by iOptics and Meta’s “I gotta buy this— wait! it’s $3,000” Iron Man interface.

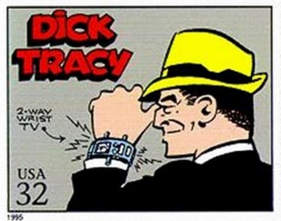

Display is also the orientation of most Smart Watches, a bit humbler than HUD but with a rich Dick Tracy history.

The Pebble brings text messages and phone calls to your wrist so you don’t have to fumble for your phone, so do the Samsung Galaxy Gear, the Qualcomm Toq, the LG, the Razer Nabu and so on.

Creation starts with the lowly pedometer that counts how many steps you take each day and moves forward to more sophisticated measurements that link a bracelet with sensors and an accelerometer to give a fuller picture of your physical activity. Some folks call this “m-health.”

The Nike FuelBand and various Fitbit devices (the Flex, the Force) are prominent examples here with Fitbit owning two thirds of the market and enjoying broad compatibility with various smart phone apps to make tracking and analyzing information easier. The new Force also has an altimeter that is useful for runners.

Creation also embraces all sorts of medical devices, from the much-covered Google Contact Lenses that will help diabetics measure blood sugar to Medtronic’s wireless telemetry that lets its cardiac pacemakers download data from a patient’s pacemaker over wifi to a home network that then sends the data directly to a doctor.

Information creation is at the heart of the Quantified Self movement that turns your body’s activity into accessible and actionable data. GroupM’s Rob Norman recently quipped on Twitter that this has also created a new genre:

“The Quantified Selfie” definition: sharing the details of your run, walk, or cycle via a wearable device to a social network. Question: why?

Of course, these two information orientations — display and creation — overlap. The FuelBand and Force creation devices also tell time; the Basis watch has more skin sensors than other fitness wearables. Google Glass can take pictures and videos— and historically we’ve seen with Facebook and smart phones that photo sharing can drive massive, exponential adoption.

But even if the same device encompasses both orientations, who we are when we use them differs in the moments when we use them for display and creation.

How we think about time

Google CEO Larry Page has said, “Our goal is to reduce the time between intention and action,” but intention, like wearables, is complex.

Deliberate intention expands over the course of time: it is conical. When we speak, for example, we intend what we say (unless we are lying) but we also mean everything that is implied by what we say even if we haven’t thought out those results in detail. (In their work on relevance Dan Sperber and Deirdre Wilson call these “implicatures.”)

Intent and action can mean our best laid plans and the work we do to achieve them, but they can also mean impulse and reaction. One gets us to the gym to work out and the other says, “screw it” and reminds us about the yummy bag of chips in the pantry. Intent is the superego. Impulse is the id. We’re all ego trapped in the middle.

Information creation wearables orient towards the future: who we want to be. They are devices of intent.

With these devices we work towards fitness goals, or collaborate with our doctors to manage our medical care. Although there is a big social component (e.g. people geographically separated sharing runs and achievements), that sharing tends to happen after the activity in question.

Wearable information creation devices, in other words, can help us get where we have decided to go: seven hours of sleep each night with 10,000 steps of activity, for example. They can help us build towards flow states, Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi’s delectable, ephemeral total immersion that happens with practice and focus.

In contrast, information display wearables orient towards the now: who I am at this moment. They are impulsive rather than considered intent.

When we strap on a SmartWatch or HUD we are inviting the universe to interrupt us, telling the mere meat space reality where our bodies live in that it and its inhabitants are less important than the invisible, alluring universe of information floating just out of sight.

These interruptions — texts, calls, reminders — are even more urgent and intrusive than email with its 67 trillion messages per year because they slide from the supercomputers in our pockets directly onto our wrists or eyes like pickpockets in reverse.

Where information creation devices give us ample chances to share later, information display devices lure us into sharing right this second without fumbling for a device. Press a button or murmur “OK Glass” and we can broadcast our passing thoughts at any and every moment.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. We live, after all, in endless progression of moments that build on the shaky foundation of yesterday and lead in a drunkard’s walk into tomorrow. And we are social beings, pack animals, who need to connect with each other: information display devices help us connect.

But we need to make thoughtful choices about our information diets just like we do with our food diets. Given my druthers, I’ll always pick the mini-can of Pringles rather than a handful of salted hazelnuts. But my bigger druther is not to look like Fat Bastard from the Austin Powers movies. So I only choose the Pringles sometimes.

An entire fitness industry exists to help people mediate between our present urges and future plans, but we don’t have that for our information diets. Wearables, paradoxically, can accelerate both our discipline and our dissipation.

Voice Recognition software like Apple’s Siri, Intel’s “Jarvis” prototype, and the compelling Samantha character in the Spike Jonze movie “Her” can also speed up our flow states or distraction.

Voice Recognition software like Apple’s Siri, Intel’s “Jarvis” prototype, and the compelling Samantha character in the Spike Jonze movie “Her” can also speed up our flow states or distraction.

These services are not wearables in the strict sense (although with Blue Tooth headsets and headphones they do extend onto our bodies), but the voice in our ear can help us find information supporting whatever task we have at hand without having to drop everything and go looking for it.

On the other hand, the revenue models for voice recognition software include interruption by advertisers. The user may be taking a thoughtful walk in the park to help himself think through an idea only to have a friendly voice chirp directly into his ear that the sneakers he was eyeing the other day are on sale at the Foot Locker store just steps away. Bye bye, idea. Hello, new kicks.

What all this means for business

As businesses think about building their own wearables, acquiring companies in the space or partnering with wearable companies it will help to think about the two different orientations— information display and information creation.

A fatty snacks company, for example, should orient towards information display when thinking about wearables since people make impulse purchases when they are in the moment rather than contemplating growing waistlines. The right advertisement on the wrist or displayed directly onto the eyes at the right instant can be powerful and profitable.

Wearables can also intervene in impulsive behavior, as demonstrated by the prototype mood bra from Microsoft that helps dieting women avoid eating driven by emotion rather than nutrition. Like I said before, these categories bump into each other.

A food company interested in health and wellness might focus on information creation, partnering with a Fitbit-like data platform to create applications that helps people use their data to achieve their goals, acting as a partner to the user and, with luck, later reaping the rewards created by the user’s loyalty.

Gigantic CPG companies with both healthy and fatty snacks could use both approaches for different products.

These different orientations don’t just work for CPG: an auto manufacturer might invite a prospective customer into a dealership with the right test drive promotion displayed on Google Glass as the prospect drives by in her old car (information display).

A maker of bed linens might connect to a body temperature sensor worn at night (information creation) to pump up the temperature in an electric blanket to keep a sleeper warm, or then to lower it when it’s time to get out of bed in the morning.

Conclusion

In “Song of Myself” (1855) the poet Walt Whitman wrote, “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes.” In the 160 years since, social scientists like Dan Ariely and Erving Goffman have shown us the twisty complications of our intentions and identities.

Although we feel like unified beings with coherent identities that transcend all the different hours in the day, we also know that we are different with our children than with our coworkers and that each new situations calls forth a different aspect of ourselves.

We are wide. We contain multitudes.

For most of us, just 10 or at most 15 years ago our first personal computing experiences were via desktop computer in the disused guest room over a mind-numbingly slow dial-up connection. Moments of instantaneous computation now spread into every corner of our lives, onto every surface in our homes and even on top of and inside our bodies.

Wearables are new sources of discipline and temptation. Thoughtful consideration about their orientations towards information and time — rather than as one category — can help us achieve our goals as individuals and businesses.

So long as we don’t get distracted along the way.

Sources & Links

Image of the Dick Tracy stamp found on “MarketingLand.com”

Image from “National Lampoon’s Animal House” (1978) found on “TheDissolve.com”

http://oldcomputers.net/apple-newton.html

http://www.unevenlydistributed.com/article/details/first-glasses-now-contact-lenses#.Ut1dwGTTl8Y

http://thenextweb.com/google/2014/01/17/forget-glass-googlex-testing-smart-contact-lens-diabetics/

http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/irvinem/theory/Starner-Project-Glass-IEEE.pdf

http://www.amazon.com/Relevance-Communication-Cognition-Dan-Sperber/dp/0631198784

http://www.ted.com/talks/mihaly_csikszentmihalyi_on_flow.html

http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/01/19/disruptions-looking-for-relief-from-a-flood-of-email/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fat_Bastard_(character)

http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2013-12/06/microsoft-smart-bra

Leave a Reply