Jonathan Haidt’s bestseller “The Anxious Generation” is a terrible book on which nobody should waste their money or attention.

Last week I had the privilege and pleasure of joining Joey Dumont on an episode of his True Thirty podcast in which we debated the merits of Jonathan Haidt’s bestselling nonfiction book The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.

Attentive readers will notice that I didn’t hyperlink to Haidt’s book, which I declined to do for two reasons:

#1: Nobody needs my help to learn about this book. As I write, it is #7 on The New York Times combined print and e-book nonfiction bestsellers list, and it has been on that list for 28 weeks.

#2: The book is terrible, and I don’t want to encourage anybody to spend their ducats on it… even with a measly hyperlink. (Sidebar: until I typed that last sentence it had never occurred to me that the word “measly” had to do with “measles,” the dangerous and unsightly disease.)

Want to know why Haidt’s book is ghastly? You should listen to our entire True Thirty conversation because we cover both sides (Joey started out as a fan, but I think I wore him down), and also because we are civil and affectionate the entire time that we are in complete disagreement. In these polarized times, that civility is a pearl of great price.

What’s wrong with the book? Representative examples follow, but before you go to them please understand that I’m not just recapitulating a podcast in this Dispatch. I’ll make different points at the end.

Haidt’s Title is The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, but Haidt never demonstrates that there is a childhood and adolescent epidemic of mental illness at all. He’s even less convincing that access to digital technologies (mostly smartphones) cause mental illness, at which point his entire argument disintegrates.

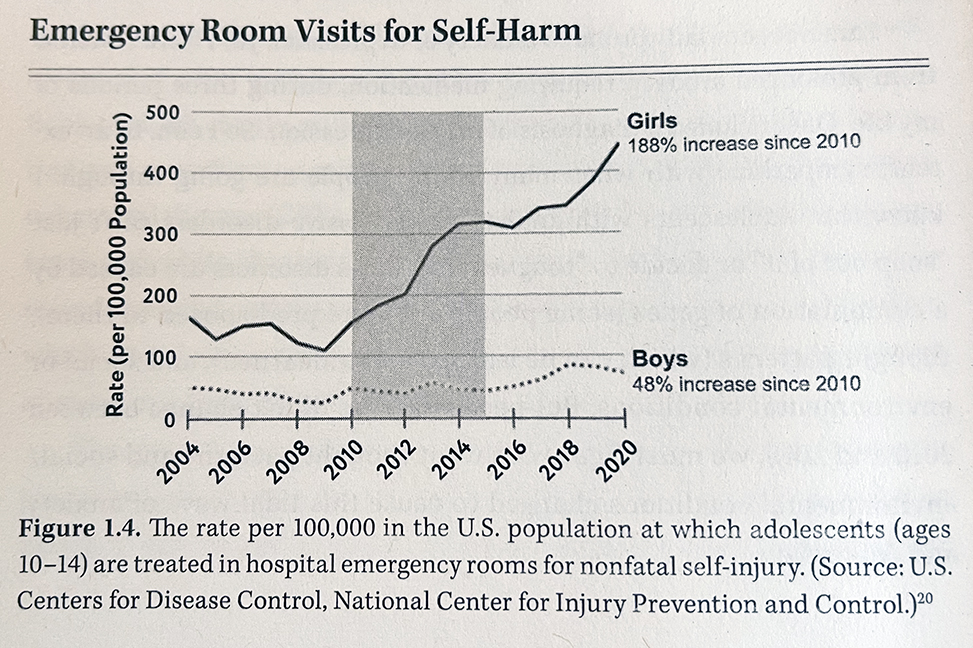

Massive exaggeration of tiny data changes. Here is a chart from page 30 of The Anxious Generation:

A 188% increase in adolescent girls admitted to hospital Emergency Rooms for self-harm! And a 48% increase for adolescent boys—that’s not a good look either. Good heavens! This is a national crisis! The sky is falling!

However, a closer look at the chart shows that it measures a rate increase per 100,000 kids in the U.S. That rate increase is from a low base that stays low. In plain English, in 2004 less than 200 out of 100,000 girls were “treated in hospital emergency rooms for nonfatal self-injury,” which is less than a fifth of one percent. By 2020, 450 out of 100,000 girls received the same treatment, which is still less than half of one percent.

Translation: More than 99% of adolescent girls still do not go to the E.R. for self-harm. Where’s the epidemic? We just lived through a real epidemic; we know what one looks like, and this ain’t it.

But still, you might be thinking, “270 extra girls going to the E.R. annually just a few years after we all met our smartphones… that’s still bad… it’s a tipping point, and we need to do something about it!”

Nope. As New York Times science writer David Wallace-Wells observed in a fantastic May 1 take-down of Haidt’s shoddy evidence:

In 2015, H.H.S. finally mandated a coding change, proposed by the World Health Organization almost two decades before, that required hospitals to record whether an injury was self-inflicted or accidental—and which seemingly overnight nearly doubled rates for self-harm across all demographic groups.

The increase that Haidt prominently features in his first chapter is both statistically tiny and reflects a change in how hospitals keep their records: not a “surge of suffering,” which is the alarming title Haidt bestows on the chapter where that chart appears.

In case you’re still tempted to give Haidt the benefit of the doubt, he uses rate increase sleight of hand throughout the book.

Why the badness of Haidt’s book matters

The Anxious Generation uses bad reasoning to make flawed arguments that nevertheless seem plausible because they represent painful but easy-to-digest emotional truths. (I explored something similar in The Plausibility Loophole a while back.)

If kids today seem different than their parents—less convinced that they have much of a chance at success, more worried about the environment, and choosing different pronouns and gender identities—then it’s a lot easier to blame smartphones than the decades long evisceration of the middle class enabled by successive administrations on both sides of the political aisle, decades of inaction on climate change that people in North Carolina and Florida are now experiencing first hand, and centuries of suppression of gender differences.

The book’s focus on kids also ratchets up the emotional stakes (“The kids! It’s all about the kids!”) while missing the point that anybody, of any age, who has a smartphone in their pocket is grappling with a supercomputer that is a frictionless conduit to digital platforms that are addictive by design.

That “by design” part is important. After 218 pages of bad science, in the book’s last 68 pages, Haidt turns to what governments and tech companies can do, what schools can do, and what parents can do in three 20 page sections.

Those sections contain some worthwhile ideas, although many of them are not original and none of them come from Haidt’s area of expertise as a social psychologist. However, what rankles me about the book’s endgame is the same-sized quality of each of those sections, which suggests that we’re all in this together—governments, tech companies, schools, and parents. That simply isn’t true. Of all those entities, the ones with the greatest resources and most single-minded desires are the tech companies.

This week, Kentucky Public Radio accidentally received and then quickly published unredacted internal TikTok documents that show the addictive qualities of TikTok on teenagers are deliberate. Earlier, the whistleblowing efforts of Frances Haugen revealed similar things about Facebook and Instagram. (Again, this is true for everybody, not just teens.)

Tech companies that create addictive platforms are not on our side anymore than tobacco companies—which take pains to put ever higher amounts of nicotine into cigarettes to make them more addictive—are on the side of smokers. On the Amoral Mount Rushmore of CEOs that created addictive products, tech company heads should be next to those of tobacco companies and Richard Sackler.

Note: to get articles like this one—plus a whole lot more—sent directly to your inbox, please subscribe to my free weekly newsletter!

* About the Title Image: I used ChatGPT’s DALL-E with this prompt: “please create an abstract image that represents the content of this essay,” and then pasted the text of the main article. DALL-E came back with the image and this explanation: “Here is the abstract image representing the theme of emotional truths that aren’t true. It illustrates the tension between emotional appeal and flawed reasoning with vivid colors and digital elements subtly incorporated.”

Leave a Reply