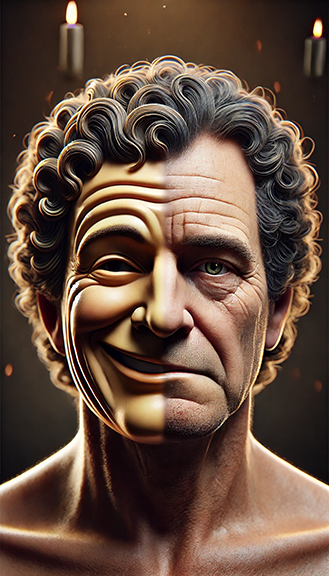

Artists can have dark sides, some alleged and some convicted. Should evil actions by artists change how we experience and judge the art?

Let’s start with two thought experiments.

#1. How would things be different today if newly uncovered evidence revealed that William Shakespeare was a pedophile who assaulted the boy actors in his company? Would we still teach his works? Would Shakespeare festivals around the world quietly change their names? Would more traditional Shakespeareans start to believe the various “Edward de Vere was the true author of the plays” nonsense conspiracy theories to distance the plays from the predator?

#2. What would happen in the art world if we learned Pablo Picasso was in reality just a bon vivant, and the true creator of the paintings we have mistakenly attributed to Picasso was Adolph Hitler? Today, the only person who seems interested in Hitler as a painter is Harlan Crow, the Texas billionaire who collects the paintings and takes Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and his wife on luxurious vacations that Justice Thomas then doesn’t like to disclose. But if Hitler turned out secretly to have been one of history’s best painters, how would that change our views of the paintings? Would it also change our views of Hitler? (I hope not.)

I pose these thought experiments because two recent articles surface similar questions about what it means when great artists, in these cases great writers, turn out to be bad people.

The question at hand is what should fans of those artists do with this news?

In the January 13 New York Magazine ($) cover story, There Is No Safe Word, Lila Shapiro explore allegations that beloved fantasy writer Neil Gaiman has sexually assaulted a lot of young women. Master, a British podcast (and also what Gaiman allegedly likes women to call him), first broke the story about Gaiman last summer. He denies everything. Shapiro has extended the coverage, including a thoughtful and painful re-reading of “Calliope” (Sandman #17), where the writer/villain, Richard Madoc, rapes the Greek Muse Calliope to cure his writer’s block. Madoc turns out to be the analog for Gaiman rather than the Sandman hero.

In the December 30/January 6 issue of The New Yorker ($), Rachel Aviv’s article You Won’t Get Free of It explores how Nobel Prize winner for Literature Alice Munro allowed her second husband to sexually abuse her daughter from her first marriage. To extend that horror, Munro used the abuse as material for her short stories. “Her writing was more real than our lives and, I think, our existence,” one of Munro’s other daughters said. As with the Gaiman article, this is not a new story, but Aviv digs more deeply.

I’ve never read an Alice Munro story, but I’ve read a ton of Neil Gaiman’s work. In grad school, my friend Cyn, another Gaiman fan, and I went to see him speak. The Sandmancomic book series is a favorite: I have every individual issue and the trade paperback collections. If I believe the allegations, then should I stop reading Gaiman? Wait to see if he gets charged and convicted? Hold onto what I have but refuse to spend money on his future writing? Not watch TV shows and movies based on his works? Those last two actions wouldn’t just be protests against Gaiman: they’d also hurt the editors, publishers, producers, and performers who create the books and adaptations.

At what point and how should an artist’s behavior affect how we experience and judge the art?

I adored the comedy of Bill Cosby as a kid; entire routines are inscribed on my memory. Cosby was convicted of sexual assault and imprisoned, freed because of a violation of due process, and still faces multiple civil suits. Few serious people doubt that Cosby is a predator. Should that change the pleasure we take in watching reruns of The Cosby Show or listening to his old comedy routines? If so, how?

How great does an artist have to be before that greatness excuses terrible behavior?

In his recent Netflix standup show Selective Outrage, Chris Rock observed:

One person does something, they get cancelled. Somebody else does the exact same thing… You know, like the kind of people that play Michael Jackson songs, but won’t play R. Kelly. Same crime. One of them just got better songs.

Jackson was accused and Kelly was convicted of sexually abusing minors. I thought about this last week when I was in Las Vegas for CES. My hotel was near the theater where Michael Jackson ONE by Cirque de Soleil was playing. A more traditional tribute show, MJ Live, is playing elsewhere. To my knowledge, neither show acknowledges the accusations against Jackson. The tributes are unironic.

There is no tribute show for R. Kelly: will there be after Kelly dies? (He’s only 58, so we won’t know for a while.)

The bad actor has to be close to the creation of the art for moral qualms to come up. Harvey Weinstein is an imprisoned predator, but I’ve never heard anybody feel trepidation about re-watching Pulp Fiction or Shakespeare in Love. Weinstein produced rather than directed those movies. On the other hand, lots of people won’t watch Woody Allen movies anymore because of the allegations that the director abused his adopted daughter, Dylan Farrow. (His marrying Soon-Yi Previn, the adopted daughter of former partner Mia Farrow, also creeps out some folks.)

For recovering English Majors like me, some of these questions give present-day urgency to old lit crit ideas. In “The Death of the Author” (1967), Roland Barthes argued that readers should ignore everything about an author’s biography and intentions, which have no bearing on the meaning of a text. Two years later, Michel Foucault counter argued (in “What Is an Author?”) that an “author function” determines how art works in society and how authorship defines a set of different works: e.g., Mark Twain’s novels, stories, and letters count as part of his oeuvre, but his grocery lists do not.

It sure would be convenient for fans of Gaiman, Allen, Cosby, Jackson, Kelly, and Munro, if we lived in a world according to Barthes, but we don’t.

Will I ever listen to “The Dentist” by Cosby, read Gaiman’s Sandman, or listen to “Thriller” with the unalloyed pleasure of the past and without a twinge of guilt and doubt? Only time will tell.

Note: If you’d like to receive articles like this one—plus a whole lot more—directly in your inbox, then please subscribe to my free weekly newsletter.

* Image Prompt: A comedy tragedy mask—with a smiling happy face on the left half and a frowning sad face on the right half—with a photorealistic human face… a 60 year old white man with curly dark hair.

Leave a Reply