As I write this sentence, Lyft’s stock is worth $56.02 per share, which means that the stock has lost 41% of its value since its March 29th debut on the Nasdaq. Likewise, Uber will make its Initial Public Offering in the coming weeks, and it can expect a similarly bumpy ride as its filing has shown, among other things, that growth has leveled off.

Reasons for the volatility of ride-hailing company valuations abound (some of which we’ve discussed in prior columns). The one I’d like to zoom in on this time is the instability of the companies’ pricing models.

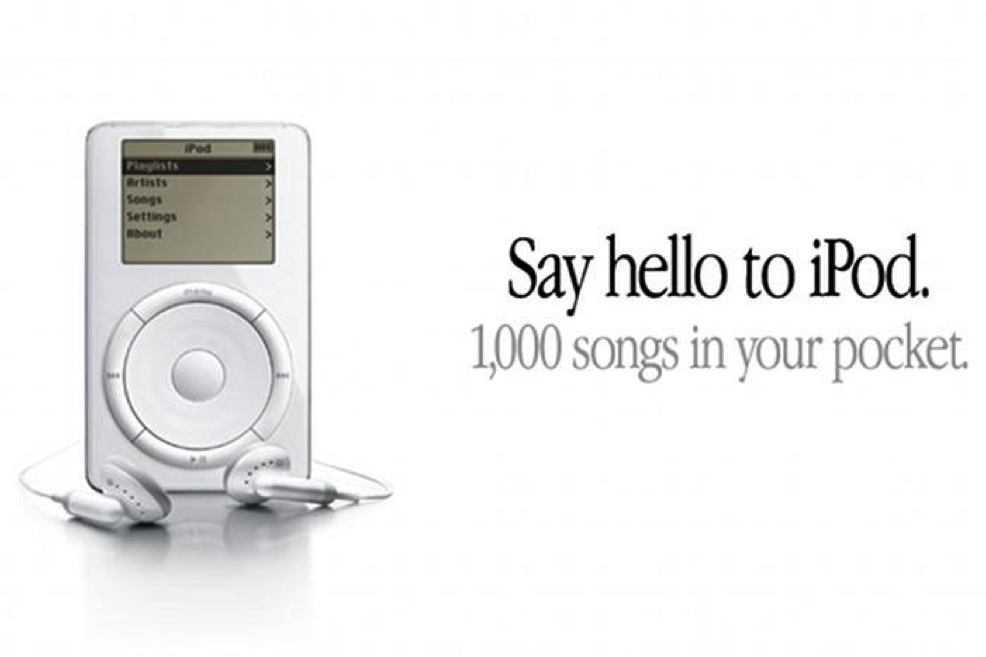

Lyft and Uber have reached their “iPod Moment,” which means that they are in the middle of an evolutionary process.

The iPod pattern

Apple release the original iPod in late 2001, celebrating the easy-to-use device with the tagline, “1,000 songs in your pocket.”

This was two years after Napster arrived online, making music piracy trivially easy and upending the revenue model of the music business. Then, in 2003, Apple introduced the first iTunes Store, which made it simple for customers to buy individual songs in mp3 format for 99 cents apiece.

The iPod as an independent device began its decline in 2007 with the release of the iPhone, which did everything an iPod did and much more.

The mp3 format was also transitory, a buy-to-download format that gave way to various forms of all-you-can-eat streaming services like Pandora (2000), Spotify (2006), Amazon Music (2007), Apple Music (2015), and others.

The pattern we saw with music is clear:

- Digitization: physical goods (CDs) dematerialize into virtual goods

- Unbundling: customers buy individual songs as mp3s, not CD collections

- Subscription: customers buy access to libraries rather than to songs.

It’s not just music. Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited platform does the same thing with books: physical books become digital book purchases, and then become subscriptions to a book service. Netflix and other OTT services do the same thing with movies: DVDs or Blu-Rays become pay-per-view rentals, and then become all-you-can eat subscriptions.

We can expect to see this pattern hold true with ride hailing.

How it will work with transportation

We’ve already passed the digitization phase, where the car dematerializes into an app that combines a smartphone, a credit card, a GPS, a map, and a matching algorithm to connect drivers with riders.

We’re in the middle of the unbundling phase, where instead of buying exclusive access to two tons of metal (a car), customers buy individual rides from Lyft and Uber.

What is to come is the subscription phase, where instead of buying rides,customers will buy monthly allotments of miles.*

Although the pattern is easiest to see with the music industry, in practice miles-per-month will look more like metered mobile phone subscriptions than all-you-can-eat media subscriptions (Spotify, Netflix).

With AT&T, Sprint or Verizon subscriptions, smartphone users select an amount of minutes, texts and data per month. If a user exceeds that amount, the company charges the user a fee and suggests changing to a different plan.**

With Transportation as a Service (TaaS), riders will select a number of miles per month. If they go farther, then the transportation company will charge them a fee and suggest changing to a different plan.

It’s also possible that the companies will give subscribers other ways to control costs by narrowing their transportation plans. Riders might subscribe to geographically-bounded plans where you can only travel within specific areas.

There might be day-part plans, where riders can save money buy not traveling during rush hour: this is the opposite of Uber’s current “surge pricing” where rides during high-demand times cost more. Day-part plans are more like Early Bird Specials at some restaurants where senior citizens who have more free time than money get a discount for dining before 6:00pm.

Why this is bad news for Lyft and Uber

The telco-like subscription models I’m predicting are great for riders but bad for the companies because they put additional commodifying pressure on the services. Uber and Lyft are already in a race-to-the-bottom price war that will continue for the foreseeable future. Telco-like subscriptions make apples-to-apples comparisons easier, which erodes any brand premium the companies might have.

For drivers, telco-like subscriptions will make it even harder for them to be savvy about extracting the most money from their hours behind the wheel. As Alex Rosenblat has insightfully shown in her recent book Uberland, drivers already have trouble controlling their workflow because of how Lyft and Uber hoard information and penalize them if they don’t accept all the rides they are offered. With this form of subscription, riders will be more focused on controlling their costs, which is bad for drivers.

Uber and Lyft have worked hard to style themselves as Silicon Valley technology companies, but in the coming days as market pressures increase and their revenue models begin to look more like those of the telcos, this myth will erode, revealing them as what they have always been.

Taxi companies.

* Uber and Lyft have both experimented with different subscription models, but none of them have taken off because they were too complicated and/or too expensive. In addition, those subscription models focus on rides rather than miles, which is like getting a smartphone subscription where you’re only allowed a certain number of calls per month.

** I’m aware that some telcos now offer all-you-can-eat unlimited plans, but this is relatively new; earlier in their evolutions they dealt with the limitations I’m articulating for ride hailing.

[Cross-posted at the Center site and elsewhere.]

Leave a Reply