Last week, a Forbes article, “Uber’s Secret Gold Mine: How Uber Eats Is Turning Into A Billion-Dollar Business To Rival Grubhub,” by Biz Carson examined Uber Eats’ impressive year-over-year growth. Since 2016, it has grown from 5% of the delivery market to 25%. It’s tracking to deliver $10 billion of food worldwide this year, and Uber will see around $1 billion of that as revenue (the bulk of the money goes to the restaurants and to the drivers).

Carson sagely notes:

Uber could certainly use the extra calories. The money-losing San Francisco-based company was valued at some $76 billion when it last raised money, in August 2018, and bankers hope its IPO, slated for later this year, could boost that to $120 billion. The problem is, there is no way Uber’s core ride-hailing business is worth that much. Its explosive growth is showing signs of slowing, and internationally the taxi service has struggled, selling its China operations to local rival Didi Chuxing in August 2016, as well as its stakes in Southeast Asia. Uber’s self-driving-car business, once considered the answer to rising driver costs, suspended testing and fired workers after an autonomous Uber killed a pedestrian in March 2018. Now, as Uber prepares to tell investors why they should buy its stock instead of rival Lyft’s, Uber Eats looks like a distinguishing factor.

As I’ve argued before, Uber is a dead company driving. Uber Eats will not save it. Any attention that Uber directs towards Eats is startup jazz hands– an attempt to distract investors from grim financial realities. One such example is a public comment on LinkedIn by Dean Nelson, head of Uber Compute:

Uber Eats has gone from 3% to 27% marketshare in less than 3 years. And that represents less than half of the 600 global cities we serve. That’s something the market can sink their teeth into!

The final sentence is code for: “Gosh we hope the market will buy come IPO time even though there’s nothing there for their teeth to bite!”

While Uber Eats may differentiate Uber from Lyft, its chief rival in the U.S., differentiation is not the same as business viability. Like Uber’s ride-hailing service, Uber Eats is a fantastic product and a terrible business. Actually, Uber Eats is an even more terrible business than regular Uber because while the ride hailing part of Uber has two disappointed constituencies Eats has three.

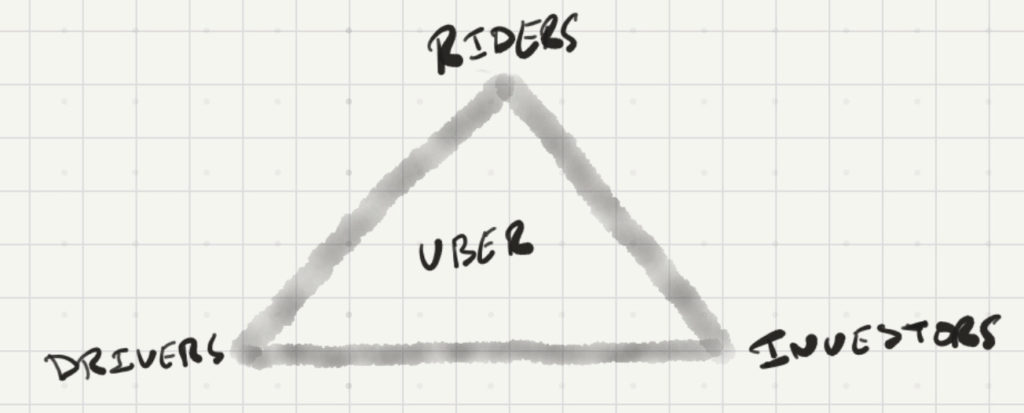

Here’s a simple sketch of Uber’s ride-hailing constituencies:

Riders enjoy a fantastic experience: seamless, intuitive, and subsidized point-to-point transportation. Investors bite their nails until the blood flows, worrying that the magical, stampede-of-unicorns $120 billion IPO won’t happen and that instead Uber will be the biggest startup bust ever. Worst off are the drivers, who absorb all the cost of the vehicle (insurance, gas, maintenance) with no health benefits.

The drivers’ disappointment doesn’t stop there because they have a satisfaction decay rate problem: Uber increases the supply of drivers in every market but rider demand doesn’t increase at the same pace. As each month goes by, many drivers find they have to work longer hours to earn the same or less money. (See this recent CNBC piece for detail about how much money drivers make.) Over time, many Uber drivers (particularly those who do it full time) have slow-burn realizations that they aren’t making nearly as much money as they’d expected.

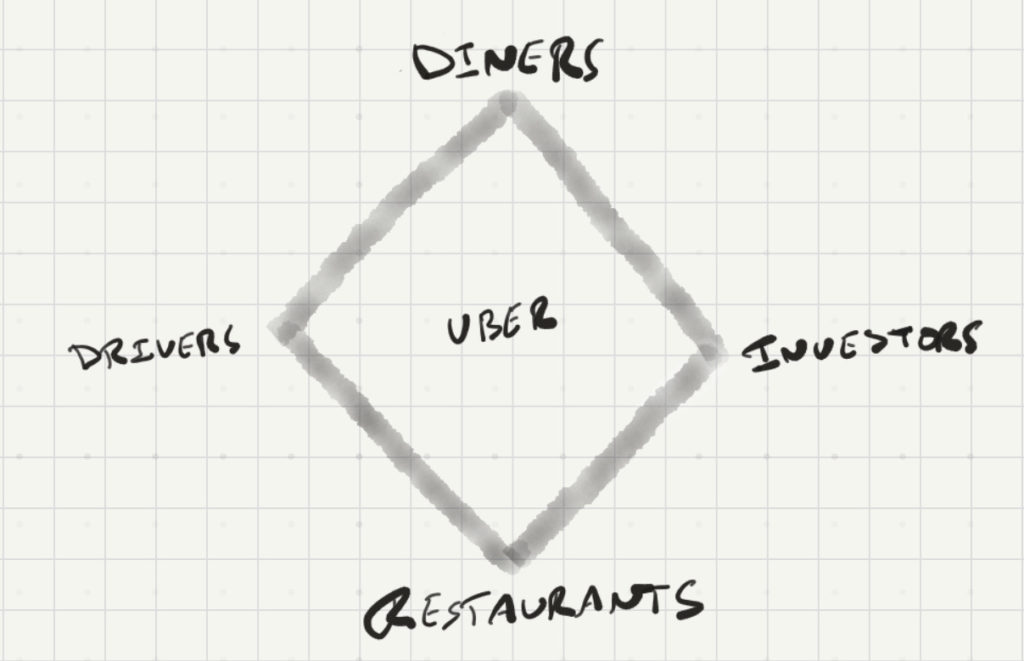

When we add restaurants into the mix the constituencies expand to look like this:

The riders have become diners. They still have a good experience, although perhaps not quite as good as the ride-hailing experience since the benchmark (going to the restaurant) is cheaper than getting restaurant food delivered. In contrast, subsidized Uber and Lyft rides are usually cheaper than taxis (which is one big factor in ride-hailing’s hockey stick growth). Savvy investors will take small comfort from Uber Eats, since it simply layers another wildly unprofitable business on top of money-hemorrhaging ride hailing. Drivers find themselves making many unprofitable little trips to deliver food instead of sometimes-lucrative long hauls to the airport.

That leaves the restaurants, which share a similarly meteorite-plunging-through-the-atmosphere satisfaction decay rate as the drivers. Why?

Home delivery is bad for restaurants.

With the possible exception of high-volume, decent-margin, QSR foods like pizza and McDonald’s, home delivery increases pressure on kitchen staff to grind out low-margin entrees while virtually eliminating the high-margin, impulse-purchase items that restaurants depend on for profitability: alcohol, coffee and dessert chief among them. (See this CNN Business article for deeper perspective.) Paying a fee and a percentage of the bill to Uber Eats or its delivery rivals quickly turns into a money-losing proposition for restaurants.

Even with fast food delivery, how likely is it that a diner will order a soft drink (high margin for the restaurant) to go with that Big Mac?

Watch for nicer restaurants to abandon delivery services of all stripes, including Uber Eats.

For lower-end, QSR restaurants, delivery will quickly become a commodity. The restaurants will own the relationship with the customer, rather than Uber Eats, GrubHub or the like. While Uber Eats may command market share today, that won’t last.

Final thoughts and clarifications

My contention is not that home-or-office delivery is a bad idea or an unviable business. I’m just arguing that it won’t do Uber much good as it zooms towards an IPO.

Softbank, one of Uber’s largest investors, has made a series of other transportation-related bets– including almost $1 billion in Nuro, an autonomous robot delivery service, just this week. This suggests a lack of confidence that Uber Eats will win the day on delivery.

I want to end by pointing out that my skepticism about Uber’s long-term viability is not skepticism about ride-hailing or delivery services per se. As I discuss in the Center’s first Future of Transportation report, Uber, Lyft and other GARS (get-a-ride services) have profoundly and unalterably changed American attitudes about transportation.

However, like AltaVista leading to Google in search and MySpace leading to Facebook in social media, Uber is likely to lead to another transportation company that will be profitable and sustainable.

Tomorrow’s winners usually aren’t today’s pioneers.

2/15/19