A study suggests that inoculating internet users against misinformation might be more successful than fact checking later, but I’m not so sure. Plus, a price sticker triggers a trip down memory lane.

The Limits of “Prebunking” in the Fight Against Misinformation

A new study in the journal Science Advances, “Psychological inoculation improves resilience against misinformation on social media,” suggests that “prebunking” online misinformation is more effective, cheaper, and more scaleable than trying to debunk misinformation via fact checking once people have already seen it. Prebunking tries to inoculate audiences ahead of time, like a vaccine, while debunking fights misinformation after exposure, like antibiotics.

The study provoked a small flurry of articles and posts, including:

- “Google Finds ‘Inoculating’ People Against Misinformation Helps Blunt Its Power” by Nico Grand and Tiffany Hsu (New York Times, 8/24)

- Prebunking is effective at fighting misinfo, study finds by Seth Smalley (Poynter Institute, 9/1)

- “Prebunking” Might Be the Solution to the Misinformation Problem by Rohit Bhargava (Non-Obvious Insights Newsletter, 9/8)

- When Teens Find Misinformation, These Teachers Are Ready by Tiffany Hsu(New York Times, 9/8)

The study finds that people who watch videos explaining various misinformation techniques (emotionally manipulative language, incoherence, false dichotomies, scapegoating, and ad hominem attacks) are less susceptible to those techniques when they later encounter them.

This seems like happy news because it means that if we can flood the internet with witty videos explaining how to spot misinformation we can stop misinformation from spreading.

I am not so optimistic for two reasons.

First, the study confines itself to online misinformation, but despite the intense efforts of digital platforms people don’t only live online. If a viewer drives around listening to talk radio or has a partisan media provider (on either side of the political spectrum) chattering in the background for hours each day, then there’s not a lot a 90 second YouTube video can do.

If you don’t know what I mean by “partisan media provider,” then a) where have you been for the last few years?, and b) check out the bottom half of the Media Bias Chartby Ad Fontes Media (disclosure: I’m an investor and advisor).

Second, the study presumes that people care about truth more than they do.

Pushing gently on the study’s inoculation analogy reveals the weakness of the optimistic conclusion: we have powerful, effective, and safe COVID vaccines that many people refuse to take them because validating their tribal identities are more important than the truth. The more partisan the viewer, the less likely accuracy is important to that viewer.

Another way of putting this is that when your opinion runs up against evidence that contradicts your opinion, you’re more likely to discount the evidence than your opinion. Despite the clear Surgeon General’s warning on all packages of cigarettes, a smoker can discount the medical evidence because the smoker’s Great Uncle Bob smoked two packs per day and lived to 100.

Psychologists call this cognitive dissonance, “the hard-wired psychological mechanism that creates self-justification and protects our certainties, self-esteem, and tribal affiliations” (page 11 of this book).

We should follow the study’s findings and increase the number of Public Service Announcements about misinformation, but that does not let YouTube and Facebook and Instagram and TikTok off the hook for being accelerants for misinformation. Nor does it let the governments of the world off the hook for regulating misinformation.

On the individual level, before you believe something that you read online, and especially before you share it with other people, think about why you want to share it. (And check out the Ad Fontes media literacy curriculum while you’re at it.)

Experience Stacks and Physical Objects

One of my ongoing topics in this newsletter is what I call Experience Stacks, which are the improvisational things that customers do over time with and around the things that companies make.

Experience Stacks are hard to talk about because we know their general shape but not their specific contents.

It’s a bit like the famous pointillist painting “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” by Georges Seurat. The closer you get to the canvas, the less sense the picture makes as it dissolves into tiny dots: to see the whole you need to stand back.

Experience Stacks are also hard to talk about because they apply idiosyncratic external context to a shared experience. These applications overlap with fan references (e.g. Easter Eggs in DVDs) or broadly recognizable cultural references, but they aren’t the same.

In earlier issues, I’ve mostly used Experience Stacks to talk about media experiences (movies, television, social media), but the idea of an Experience Stack is also a useful tool when talking about physical objects.

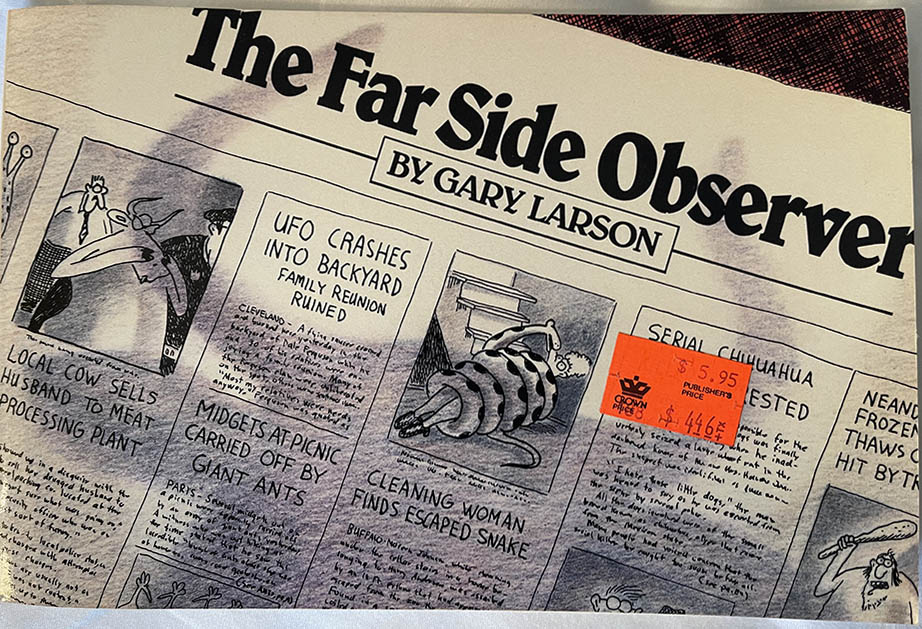

For example, while visiting family last week I plucked The Far Side Observer off a shelf:

This was the 10th collection of Gary Larson’s inimitable, weird, and hilarious comic strip, first published in 1987. Before opening the book, the orange sticker caught my attention.

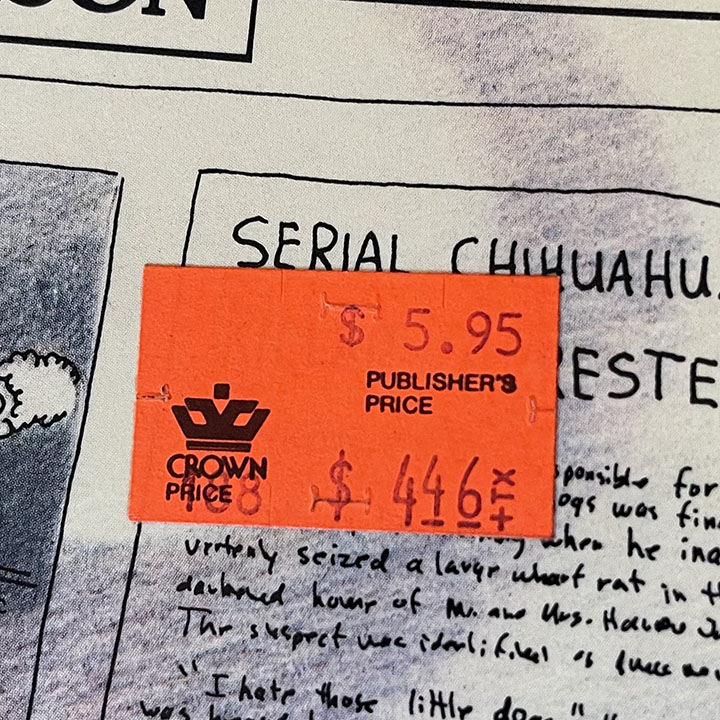

Here’s a close-up:

For those too young or insufficiently bibliophilic to remember, in the final years of the twentieth century Crown Books did to independent bookstores what Amazon later did to Borders: it undercut the independent bookstores on price and drove them out of business. One big difference between Crown and Amazon is that Crown had a narrow selection of titles, which flattened the available books to buy. In contrast, Amazon has an infinite selection that caters to the long tail, but I still miss browsing in physical bookstores and rejoice that I live near Powell’s.

Like Proust tasting his madeleines, that orange sticker involuntarily pulled me back in time. I don’t know that I was the family member who purchased the book, but I could see the aisle (two thirds of the way in and on the right, but not all the way to the right) where it would have been on the shelf at the Crown Books on Van Nuys Boulevard.

The orange sticker makes an Experience Stack visible, which is unusual. It is an external marker of when that copy of The Far Side Observer entered my family’s possession and when it became a block in my Experience Stack for The Far Side. Keeping that sticker on the cover distinguishes our copy of the book from most other copies, giving our copy a tiny, fragile amount of what the early 20th Century philosopher Walter Benjamin called “aura.” The aura is tiny and fragile because all it takes to erase our awareness of it is peeling off a sticker.

People do things with their experiences, and they seek out new experiences that are both novel and that build on their previous experiences. Companies that understand this can make it easier for people to build their Experience Stacks even though the company cannot see the content of those stacks.

This can be a competitive advantage.

Note: to have articles like this one–plus lots of other goodies–delivered to your inbox, please subscribe to The Brad Berens Weekly Dispatch!

Leave a Reply