Online scams are a $500B annual “industry.” Here are a few ways to protect yourself from being the next victim.

There’s a thin line between paranoia and sensible precaution.

When it comes to online scams, it’s hard to see the line because it’s squiggly, jagged, dotted, and looks like the EKG of somebody on a quadruple espresso, three Twinkies, and crystal meth.

The short version of this Dispatch is that you should always be skeptical of inbound communications. That means you should think twice about every text, email, and social media message—even if something looks like it’s from a friend.

That’s a big burden, I understand, so here’s an even shorter version: don’t click on anything that comes to your phone, tablet or computer.

It is hard to believe, but online scams represent a $500 Billion annual “industry” that takes in people worldwide from every education level, income level, political orientation, region, religion, and community. The Economist ($) has a thorough briefing about this from February as well as a fascinating podcast series, Scam, Inc.

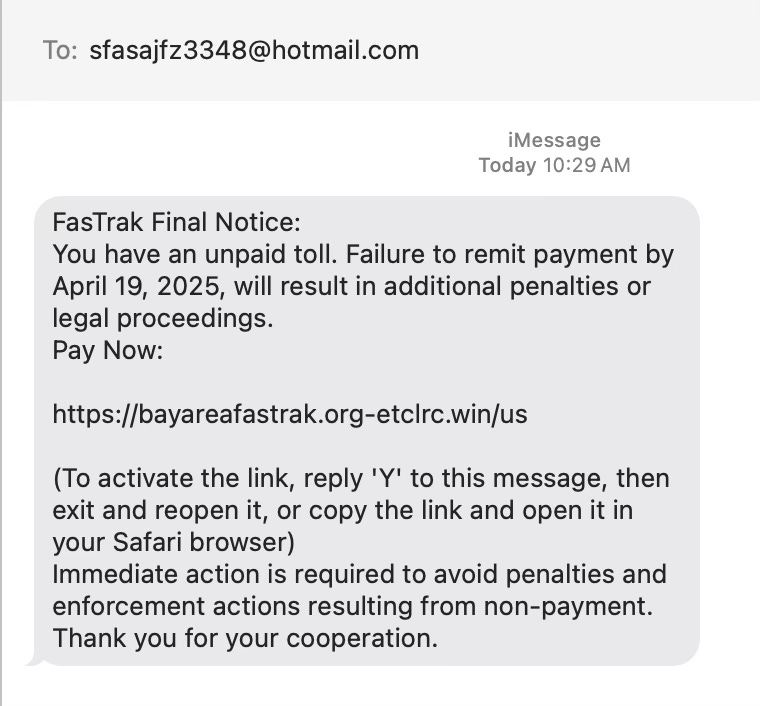

I created this image using ChatGPT.*

General Hints

Never react quickly, even if the thing the criminal on the other end of the phone says induces panic. One friend got a call saying that her daughter had been kidnapped and the criminals required $50,000 to release her. Terrified, she started calling the bank. The lucky thing that stopped her was when her son happened to arrive. “I just talked with Sis two minutes ago; she’s fine,” he said.

This was before cheap voice cloning technology made it easy to mimic somebody’s voice. Today, even if you get a call with a convincing voice of a loved one on the other end, text that loved one in the background before you take the kidnapping story seriously.

Phone a friend: if you have even the slightest doubt about an email, text, or phone call, call another person and talk about it. Don’t be embarrassed.

Never send money to anybody you haven’t met face to face, in real life (that is, not on Zoom). Even if you’ve been chatting with that person for a long time, even if you have spoken with them in real time, if you haven’t met them face to face, don’t give them money.

Be particularly suspicious of anything having to do with cryptocurrency.

Specific Tips

Here are some ways to identify quick hit scams (I’ll talk briefly about long cons at the end).

1. Always go the long way around. If you get an email that looks like it comes from your bank, has an alarming message about an overdraft or a zero balance in an account that should be dripping with dough, and has a handy “click this link to review your balance” option, don’t click on it. It’s probably a scam.

Do you remember the kids game Chutes and Ladders (some folks grew up with the icky alternative Snakes and Ladders)? The link in the scammer’s email is a chute or (shudder) a snake: the scammer is hoping you’ll be so worried about your money that you’ll click the link to resolve the problem at once.

If you were to click on it—and remember, don’t click on it—the website you land on will look exactly like your bank’s website, and it may even have a URL (Universal Resource Locator, i.e., the web address like www.bofa.com for Bank of America) that is close to the real one like www.bofa.online.

Take the ladder instead: pull out your credit card or debit card and look for the website address on the back, type that into your web browser, and then look for a help or support option. You can also call the number of the back of the card.

This isn’t just for email: you should also be careful about text messages.

2. Look carefully at who is texting and where they want you to click (don’t click!). For example, I received this text the other day:

FasTrak is how toll bridges in the Bay Area collect tolls without having to pay pesky humans to work in little kiosks blocking the way to the bridge. (It’s disgusting that a government agency fired humans in favor of robots, but that’s outrage for a different piece.)

Why would a text to me read “sfasajfz3348@hotmail.com” in the To: field? Answer, it doesn’t come from FasTrak at all, nor does it know who I am. It’s a spray-and-pray scam.

3. Examine links. With the FasTrak scam, here’s the link it wants me to click:

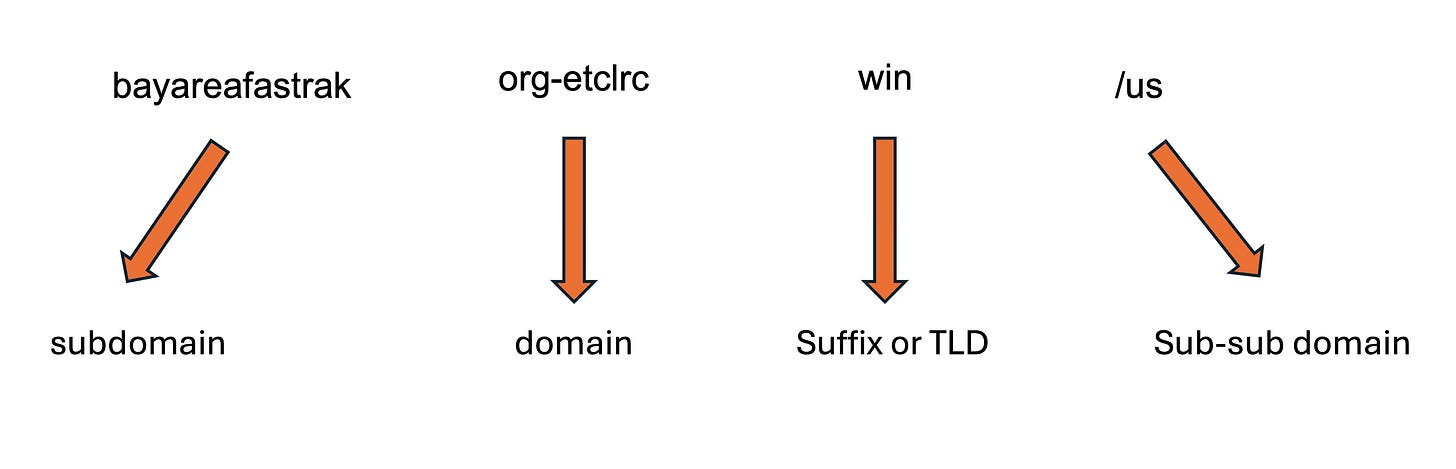

https://bayareafastrak.org-etclrc.win/us

Remember, don’t click on anything, but it’s still worth examining links because that will train your eye to spot scammers.

The scammers want you to focus on bayareafastrak.org, which is the actual website for paying FasTrak tolls. However, the real scammer website is org-etclrc.win.

Here’s how the different parts of that link fit together:

The subdomain on the left is “bayareafastrak.” Subdomains are one way of breaking a website up into different departments. You might see psych.universityname.com for the Psychology Department at your local university versus english.universityname.com for the English Department. Or for a service business you might see sales.businessname.com versus service.businessname.com.

The main domain is org-etclrc, the way the main domain for amazon.com is amazon or how the main domain for disney.com is disney.

The suffix or TLD (for Top Level Domain) on the right indicates the general sort of website it is: .com for commercial, .org for nonprofit, .uk for sites in the United Kingdom, etc.

.win domains are for gambling, e-sports, and other competitions: not regional toll bridges.

the /us on the far right is another way of breaking up websites: you’ll often see /en for the English Language part of a website or /es for Spanish, /fr for French, and so on.

Just by looking carefully, you can spot a scam.

The trick is to take the time to look carefully.

4. When in doubt, just turn off the machine. I recently heard about a new shock and awe scam tactic in which scammers will get a piece of malware onto a victim’s computer or tablet that turns the device into a siren, shrieking a high-pitched, disorienting noise.

At the same time, the screen reads, “Do not turn off your computer. Hackers have taken over your machine. Call this number, and we’ll help you fix the problem.”

After a few minutes, the siren will drive anybody crazy and make them desperate to make the noise stop, which is when victims make the tragic mistake of calling the number. Don’t call the number.

Ignore all of this.

The number they want you to call connects to the hackers who caused the problem in the first place. They want to steal your money by pretending to be helpful techs who want to fix the problem, and then they ask for your bank information.

Just turn off the machine. If you can’t turn off the machine, put it in another room and shut the door.

If you’re not technical, which most people aren’t, then call a friend who is technical, a teenager, or your local computer fixit shop. There is a chance that your computer will be garbage or expensive to fix, which is a drag, but it’s better than having your life savings stolen.

Extras

The tips I’ve shared are for quick hit scams, and they barely scratch the surface.

Long cons are a different story. The unsettling term of art for long cons is “pig butchering,” which The Economist ($) briefing and podcast series from February both dig into at length. If pig butchering sounds familiar, a February 2024 episode of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver explored it. You can find it free on YouTube.

Beware the Words With Friends Scammers: this is a piece from 2018 that may be the most-read thing I’ve ever written.

I covered “the middle of the night call”—another scam—back in 2022.

In New Cracks in Reality (August 2024) I explored how AI will supercharge fraud and scams.

“Phone a friend” is my general advice whenever something online (or off, frankly) seems either too good to be true or vaguely alarming. In My 2023 Prediction… or Prayer (December, 2022), I dug into why and how to do this, with a related discussion of the idea of “Fair Witnesses” from Robert Heinlein’s classic novel Stranger in a Strange Land.

The more educated a person is in one area, the more likely that person is to fall for an online scam. This phenomenon has many names, including the Expert Fallacy, but my favorite is ultracrepidarianism.

Note: if you’d like to receive articles like this one—plus a whole lot more—directly in your inbox, then please subscribe to my free weekly newsletter.

* Image Prompt: Please create an image that captures the essence of this essay. (I took the easy way this time.)

Leave a Reply