Regular readers know that I’ve been taking Ozempic for the last few months because I have Type 2 Diabetes and also have struggled to lose weight. I’ve shared My Ozempic Journey from time to time (this issue is one of those times) and also talked about the Center for the Digital Future’s research about Ozempic Disruption generally.

Since I started, my results have been slow but positive: my blood sugar is looking better, and my weight has come down slowly. I don’t like to weigh myself, but I can now wear shirts that I couldn’t as recently as last summer. The other day, La Profesora said, “that shirt is too big for you to wear,” which was both encouraging and dispiriting because now I have to go buy shirts.

My pants are also increasingly baggy. That could be because of the Ozempic, but it also could be due to a Berens Family malady known as GALN or Galloping AssLessNess, which I have inherited from my father. (Thanks, Pop.) In life, some mysteries never find answers.

Last week, a few days after I called in a refill to get a new pen to inject Ozempic, the pharmacist at Rite-Aid (it’s the closest pharmacy to my house) called with startling news. “We don’t fill prescriptions for Ozempic, Mounjaro or any of the others anymore because we lose money with each sale.”

“Really?” I asked, incredulous. “Can you tell me what other pharmacy might still carry Ozempic?”

“Try Costco,” the Rite-And pharmacist said in a brief Miracle on 34th Street exercise.

I stopped by Costco after the gym later that day. Costco still carries Ozempic (phew!), so I transferred the prescription and then picked it up the next day. No biggie.

Pharma Alphabet Soup

I didn’t understand how it’s possible that Rite-Aid could lose money selling Ozempic. As with any prescription, the receipt from the pharmacy has information (I can’t call it an explanation for reasons that will soon become less murky although not clear) that lists two prices:

- The Usual & Customary (U&C) price

- The price that a person with health insurance pays—meaning, the “co-pay.”

This is where things get confusing.

I had always thought that U&C was what the pharmacy charged an insurance company, what the insurance company would then pay, less the co-pay.

Oh boy was I wrong.

U&C means the rack rate: what a person with a prescription but with no insurance would pay if she or he walked up to a pharmacy counter and said, “I want to buy this, please.”

The U&C for the kind of Ozempic that I take is $1,305.99.

As near as I can tell, U&C is a fantasy number: no sane person would ever pay it; no pharmacy is likely to get away with charging it unless the customer is paying no attention.

U&C is different from WAC, the “Wholesale Acquisition Cost,” that pharmacies and the uninsured pay to Novo Nordisk, the pharmaceutical company that makes Ozempic. The WAC for Ozempic, per the Novo Nordisk website, is $997.58.

WAC is a more practical number, close to what an uninsured person would pay if they walked up to a pharmacy counter with no insurance, no coupons, no rebates, etc.

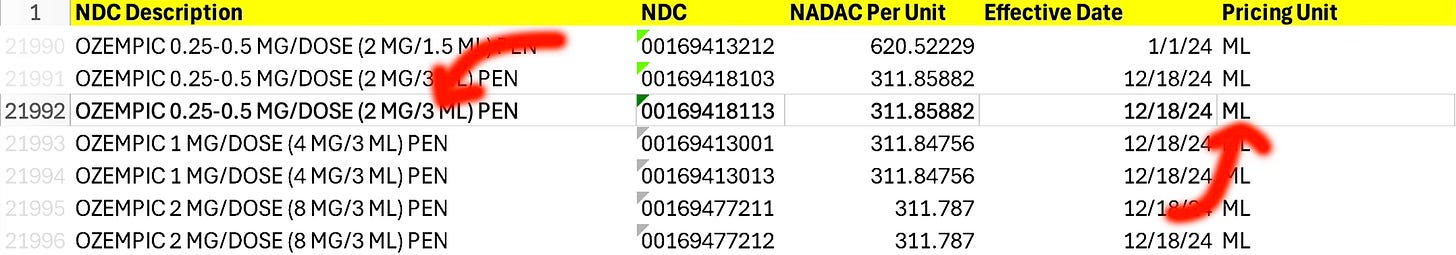

Then there’s NADAC, the “National Average Drug Acquisition Cost,” that Medicaid tracks monthly. To get this information, I had to go to the Medicaid site, download the gigantic April 2025 spreadsheet, and then open it in XL to find the Ozempic information alongside thousands of other drugs:

This, too, is difficult to interpret without doing some arithmetic because the price listed is per milliliter with three milliliters per pen, so the NADAC price for the kind of Ozempic I take is $311.86 x 3 = $935.58.

When I searched my prescription on GoodRx (a comparison site for meds), it checked 13 pharmacies in my area with retail/no-insurance prices per pen ranging between $964.99 (Costco) and $1,197 (Capsule Pharmacy, of which I’d never heard until that click).

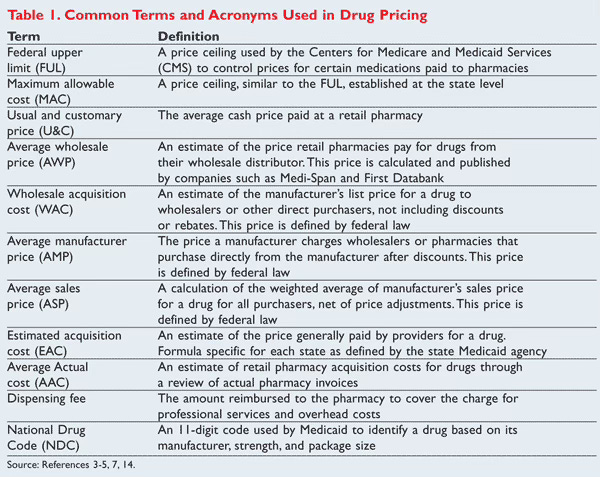

All this, by the way, is the simple version. You can get a sense of how complex drug pricing gets by taking a quick look (don’t linger; you’ll get a headache) at this chart from US Pharmacist, a trade journal:

None of this explains why Rite-Aid loses money on Ozempic

As I dug deeper, I learned that pharmacies buy meds from drug companies at or around WAC.

When a customer has insurance, the pharmacy charges the insurance company, but how much the insurance company pays out to the pharmacy depends on the rate that a Pharmacy Benefits Manager (PBM) has negotiated. The payout can be less than the cost of the drug, depending on the PBM contract, and the pharmacy cannot increase the cost of the co-pay to make up the difference.

The reason Rite-Aid in particular has stopped filling Ozempic prescriptions probably has to do with the pharmacy having to sell off Elixir, its own PBM, as part of its deal to emerge from bankruptcy, which concluded just a few months ago. Without Elixir, Rite-Aid has less leverage, so the pharmacy’s recourse is to stop selling unprofitable products even though in doing so it alienates its customers.

As recently reported by WSJ ($), big pharma manufacturers have successfully spent a lot of money throwing the blame for high drug prices on PBMs. Doing this obfuscates the greed of the pharma companies themselves as they set WAC at eye-poppingly high prices. (Their usual explanation/excuse for these prices is that for every successful drug they bring to market they lose billions in R&D for other drugs that fail.)

PBMs are profitable businesses because they are secretive. The old business saw that there’s margin in mystery applies to PBMs because they don’t disclose rebates, discounts, and other negotiations. This is why increasing PBM transparency is a bipartisan issue, which also means that Big Pharma has been energetically lobbying both sides of the aisle.

The short version? The numbers on your pharmacy receipt (U&C and your co-pay) look like they are conveying information, but those numbers are an exercise in obfuscation. “Look at how much money you saved!” the receipt implies. In reality, pharmacy customers have no idea how much their pharmacy spent to buy the drugs, how much money the insurance pays the pharmacy that dispenses the drugs, and what the PBM middlemen get out the process.

Action or Theater?

On April 15, President Trump issued an executive order (with no force of law) about reducing drug prices for Americans. This included language directing the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to take action around “Improving disclosure of fees that pharmaceutical benefit managers (PBMs) pay to brokers for steering employers to utilize their services.”

However, just 12 days earlier on April 3, the administration ordered HHS to reduce spending by 35% on top of cutting 20,000 HHS jobs just days before on March 27.

How, I wonder, will a much-reduced HHS (run by a man skeptical of modern medicine) find the resources to act on reducing drug prices for ordinary Americans?

Note: To get articles like this one, plus a whole lot more, delivered to your inbox, please subscribe to my free weekly newsletter!

* Image Prompt: “A comic book style picture of a middle-aged white man with salt-and pepper hair, wearing glasses. He walks along a woodland path with a stick over his shoulder. At the end of the stick is a cloth that contains his belongings.”

Leave a Reply