My search for a 22-year-old comic book series led to a realization about where satisfaction comes from… or doesn’t.

A quick word about Experience Stacks before we move on to our top story. Experience Stacks are the different contexts that a customer, user, or audience brings to a product or story. People improvisationally shift from context to context during experiences, which is one of the key differences between analog (human) thinking and algorithmic (AI) thinking. That’s all you need to know about Experience Stacks to understand this article, but you can dig into all my pieces on this topic if the spirit moves.

“Doomscrolling” on social media describes falling down a rabbit hole into an endless, mesmerized sweep on your platform of choice (Instagram Reels often suck me in, and I’m scared of TikTok), flicking from one thing to the next while training the algorithm to serve you more and more of the stuff it calculates will keep you there longer and coming back more often. This is like filling out a survey for a serial killer about the routes you take home from work, your favorite grocery store, and that coffee shop where you like to spend time daydreaming. It doesn’t end well.

But doomscrolling can also reveal information you want in real life. This is one of those stories; it is also a story about where satisfaction comes from and how it can fail to arrive.

When I was five, my mother—worried that I hadn’t already become an avid reader—introduced me to comic books. More than half a century later I still love comics, and the only reason my garage hasn’t collapsed under the weight of thousands upon thousands of comics is that a few years ago I started reading comics digitally.

Back to doomscrolling: the Instagram algorithm has figured out that I’m a comics nerd and will share images that other comics nerds have posted. While this sounds pleasant, it is typically an exercise in frustration because the posters so rarely share what comic the image comes from. If such an image is both interesting and I don’t recognize it, then I have a problem. Google Image Search is the solution of first resort: I download the image to my desktop or phone, drop it into Google Image, and hope that somewhere else on the internet somebody has shared the same image with attribution. It works some of the time.

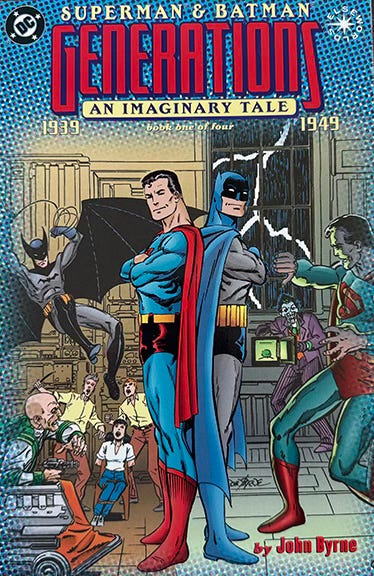

Last year, slouched in my chair and doomscrolling when I should have been doing something else, I happened across an arresting image. It was a drawing by legendary comics artist and writer John Byrne, and it was also from his series: Superman & Batman: Generations. Here is the cover of the first issue from 1999:

The conceit of the series is that both superheroes begin their adventures in 1939 (when the characters first appeared in comics in real life), and each issue happens 10 years later. Unlike in most superhero comics, the characters age and change with each decade, having children and grandchildren, some dying, etc.

The series and Superman & Batman Generations II, its sequel (or paraquel, which I’ll get to later), are among my all-time favorite comics—so much so that they live on a bookshelf in my study rather than in the garage.

Digression: the subtitle in the first issue cover image above, “an imaginary tale,” has always amused me. It is code for “this story takes place outside the current continuity of interconnected stories happening across our comic book company right now,” and “Elseworlds” is the DC Comics imprint that signals this kind of story. But what is the opposite of an “imaginary story” in comic books? It’s not like other comics are somehow real or not imaginary! (End of digression.)

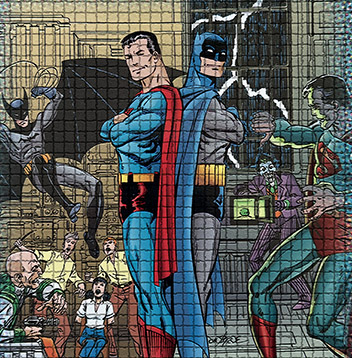

Here is the image I ran across on Instagram:

Although I recognized Byrne’s style, I did not recognize the scene. Had I forgotten this sequence? That was unlikely, but I pulled out both series and skimmed through them afresh. No dice.

Intense Googling ensued and yielded my answer: there was a third Superman & Batman: Generations series that I had never read! The first two series were four, extra big, prestige format issues each. The third was 12 normal format issues. DC had published them from 2003 to 2004.

I reached for my iPad and dug into the DC Universe digital comics app. No dice. I searched for a trade paperback that collected all 12 issues. No dice. I did find an omnibus that collected all three series, but the list price was $75, and it would require buying again the two series that I already own. I didn’t want to do that.

Plus—and this was so gratifying, even thrilling—now I had a quest.

Quests, Experience Stacks, and the problem with eBay

I love quests! I love having a book or album or shirt or whatever that I can’t simply stream or order online. I love the hunt, the prowl, the thrill of discovering a new shop that might or might not have the object of my quest.

The internet, and especially eBay, have ruined this. Want an obscure DVD or old issue of MIT Technology Review, handmade leather notebook from India, wheel for a Tesla 3, or 1970s-era pin-up photo of Lynda Carter? You’ll find them on eBay. What used to be the end of a quest has turned into the near end of quests altogether, which is why finding a quest in 2025 is rare and special.

Quests imbue mass-produced objects with individual meaning, like what the philosopher Walter Benjamin calls “aura” around great works of art in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” or how the anthropologist Daniel Miller explores the way people organize similar purchases in unique ways in Material Culture and Mass Consumption.

For my kids and their friends, thrifting does similar work. Gen Zers don’t only thrift because they are young and don’t have much money or because they believe in sustainability. All of those things are true, but I believe it’s also because things they find at thrift shops are less common than things they can get at Target or on Amazon.

The combination of an object, the place you buy it, the people you are with when you buy it, and how that object connects to other things you own (other things in your wardrobe, other comics in your collection, etc.), all combine to form an Experience Stack that adds contingent, extrinsic value and meaning to the thing you’re buying.

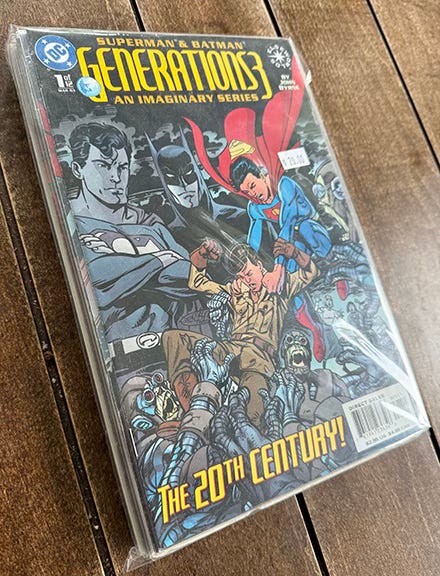

I decided not to look on eBay for issues of Superman & Batman: Generations III. Instead, I dug around the comic book shops in Portland. I quickly found the first three issues, but I didn’t read them because I wanted to complete the set first. Over the following months, I managed to get nine of the 12 issues, each costing around three bucks:

I was only missing #4, #6, and #12. The hunt continued, but I had little luck. Weak-willed, I contemplated eBay but then tightened my resolve. I wanted to find those remaining issues myself.

January arrived. On a rare sunny day, La Profesora and I took a scenic walk around Vancouver Lake just across the state border in Washington. After, I asked to make a pit stop at I Like Comics, which I’d heard was a terrific shop. (It is.)

After saying hi to the guy at the counter, I sifted through a prodigious amount of back issues, looking for my last three. No dice. I was about to give up, but there was a rack of pull-out cabinets full of complete runs in the back room, underneath endless longboxes full of individual issues. I squatted down and crab walked until I reached the S section and pulled out each of the drawers in succession.

There it was. The complete Superman & Batman: Generations III series bundled in a single plastic bag for twenty bucks.

The comics weren’t in the same near-mint condition as the individual issues I’d collected, but there they were. I asked the guy if I could only buy my three missing issues, but he wouldn’t break up the set. Fair, but galling.

I bought the collection, brought it home, and put it on the pile of “read soon” books on the table to the left of my desk. I didn’t move the individual issues out of the closet to group with the new complete set.

The complete set stayed on my “read soon” pile. And stayed. And stayed. Gathering dust.

Nearly six months later, I still haven’t opened the bag.

Sure, I’ve been busy, but I’ve read many other books and comics and articles in that time, but not Superman & Batman: Generations III.

I still want to read it. The second series was a paraquel (see, I told you I’d get to it), which is like a sequel. With a sequel, new action comes after a story ends. A paraquel has new action that happens alongside a story, but either at a slight distance or from a different point of view. Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead is a paraquel for Shakespeare’s Hamlet. From what I can tell, the third series is another paraquel, which sounds complex and interesting.

So why haven’t I read it?

Buying that complete set felt like cheating. I’d spent around $27 on nine issues and wanted to spend another nine bucks on the last three. Instead, I paid an extra $11 and now had lots of duplicate copies that I didn’t know what to do with. By buying the complete set, I denied myself the triumphant moment of finding that one last issue that would then have earned me a quiet couple of hours with the entire series.

The Experience Stack that I’d been building around my quest crumpled like a house of cards.

Final thoughts

Usually, when we talk about what an object, story, or artwork means we’re talking about what the author intended or how the thing operates in culture. (I talked about this a bit here.)

Experience Stacks are about a more personal, highly contingent sort of meaning that we build using the object of the experience itself, the context of first and subsequent interactions with the experience, and also the container or containers of the experience.

Although Experience Stacks are not exclusively analog, it’s harder to construct one in a frictionless, purely digital environment.

I don’t know when I’ll get around to reading Superman & Batman: Generations III. When I do, I’m confident that I’ll enjoy it, but I’m also confident that I’ll enjoy it less than I would have if I’d completed my quest.

I’ll let you know.

Note: to get articles like this one—plus a lot more—directly in your inbox, please subscribe to my free weekly newsletter!

* Original image: copyright DC Comics, 1999.

Leave a Reply