In this election season when we’re all getting hundreds of daily messages attempting to persuade us, most aren’t effective. I return to earlier work about persuasion with new thoughts.

I’ve been writing about persuasion for years, long before the birth of The Dispatch. Back in August of 2023, I tried to decant a lot of my thinking into “Keyword: Persuasion,” which you’ll find reprinted below. That piece extended earlier work about how people decide with their hearts and then later reverse engineer justifications for their emotional choices with their heads.

What’s been on my mind lately is how little persuasion is actually happening in the current election. Folks like me who follow political news closely have jaws agape at the very notion that there still are undecided voters. How is this possible?

Before Joe Biden dropped out of the race, I could see how people who don’t pay attention to the news would shrug because they didn’t see much difference between one elderly white male candidate and another. But since it has been a Harris v. Trump race, the differences have been clear.

John Heilemann, in a Puck podcast that I’ve referred to previously, observed that the election hinges on irregular voters rather than undecided voters. These are folks who don’t think their vote matters and/or don’t think either party will do anything to benefit them. Persuading them to vote in the first place, rather than vote in a particular way, is the big challenge.

At this point, I can’t imagine a Republican persuading a Democrat to vote for Trump, and I can’t imagine a Democrat persuading a Republican to vote for Harris. This is a failure of my imagination. It also indicates that going into a conversation about the election with one’s political party as the key identity frame is a mistake.

What’s an identity frame? This is an idea originated by the great 20th century sociologist Erving Goffman, who realized that our identities change as our contexts change. I’m a different guy with my kids than with my parents, or friends, or colleagues, or strangers. Going to your high school reunion activates an old context and therefore an old identity frame.

If I’m right that the most important aspect of persuasion is empathy (see below), then our inability to have political conversations with people on the other side is a kind of empathy crash from which recovery is difficult. (Reading Arlie Russell Hochschild’s most recent books is a good first step.)

One way to get around the empathy crash might be to approach conversations by leaning into a different identity frame than political affiliation. My cousin D and I are on the opposite sides of the political aisle. I am deeply grateful that our family bond has resulted in a long, civil series of text exchanges about politics. D and I don’t seem to be convincing each other of much, but at least we’re communicating.

Here is my August 2023 piece about persuasion.

Keyword: Persuasion

The word “persuasion” gets a bad rap because it sounds like a con job where the persuader pulls one over on an unsuspecting mark. P.T. Barnum famously had a sign that read “This Way to the Great Egress!” that fooled circus goers into going through a door to see another carnival exhibit, “the egress,” only to find themselves having exited the carnival. They had to pay again to get back in.

That’s not persuasion. That’s just lying.

The most important aspect of persuasion is empathy. You have to know about the other person’s life, job, likes, dislikes. The more you know, the easier it is to co-create a reality that includes things that you both want.

Usually, businesspeople talk about friction as a bad thing, but with persuasion friction is your friend. The more embodied and immersive a conversation you have when you’re trying to convince somebody to do something, the more likely you are to get their attention, and attention is the first step towards persuasion.

It sounds like I’m only talking about one-to-one persuasion, but I’m not. Advertising works by taking categories of things that lots of people want and then constructing narratives around how their products might fit into those desires. The more friction in the environment where somebody experiences a narrative, the more likely they are to engage. You are, for example, more likely to buy a souvenir t-shirt at a concert than to order one online later because you want to remember the concert and be able to show off that you were there when you wear the t-shirt. Disneyland is a massive exercise in immersive persuasion that people pay big bucks to visit. It’s not one-to-one.

The disembodied frictionlessness of digital media means that it’s harder to persuade somebody online than in person. When you get hundreds of emails each day, the horde drowns out individual voices yielding little attention.

Know the stakes

In addition to empathy and attention, it’s also important to know the stakes of the other person’s decision because the higher the stakes, the greater the effort you need to make. Your stakes as a reader of this newsletter are low. The Dispatch is free, so there are no economic stakes. If you’ve read previous issues, then (I pray) you’re moderately confident that you’ll smile at least once and go, “huh… interesting” at least once. Likewise, if I’m going to be in your town and suggest we grab a cup of coffee, those too are low stakes.

However, if I’m asking you to fly from San Francisco to New Delhi in order to give a talk at a conference I’m producing, and if I’m not offering you a speaker fee, then I’d better have a highly customized, thoughtful, and compelling reality I want you to co-create with me.

Some years ago, I did just that with my friend S, a senior marketer who was born in New Delhi. I knew that if I just asked him to speak, then his primary consideration would be his schedule. Instead, I said, “your mom doesn’t understand what you do for a living, and she still lives in New Delhi, right?” He said yes. I then pitched him on a keynote to which we’d invite his family to be in the audience, where they could both get a sense of what he does and see the esteem his industry has for him.

S couldn’t say no to that.

By the way, persuading somebody to do something isn’t the end of your job as a persuader: it’s the start. I was the MC for that show in India, and before I welcomed S to the stage I pointed to his mom in the audience. She stood up with an expression of fierce pride that still makes me tear up when I think about it.

The Persuasion Quadrant

In addition to empathy and attention, persuasion also requires understanding what kind of response you’re trying to elicit. Despite what classical Economics tells us, people generally aren’t rational actors. That doesn’t mean that they’re irrational actors. It just means that people tend to decide with their hearts and then justify those decisions with their heads later.

If you follow that cadence and lead with a heart reason followed by a head reason, then you’re more likely to persuade the person than with the reverse sequence.

That’s what happened with my friend S. I led with an appeal to his heart, but I backed it up with an additional appeal to his head since this was a major conference with lots of colleagues and press and other things speakers like. (Elsewhere, I’ve talked about this sort of thing as “the two-strategy strategy,” which will probably become another Keyword entry at some point.)

People also respond more quickly to loss than to gain. Fear is more powerful than greed.

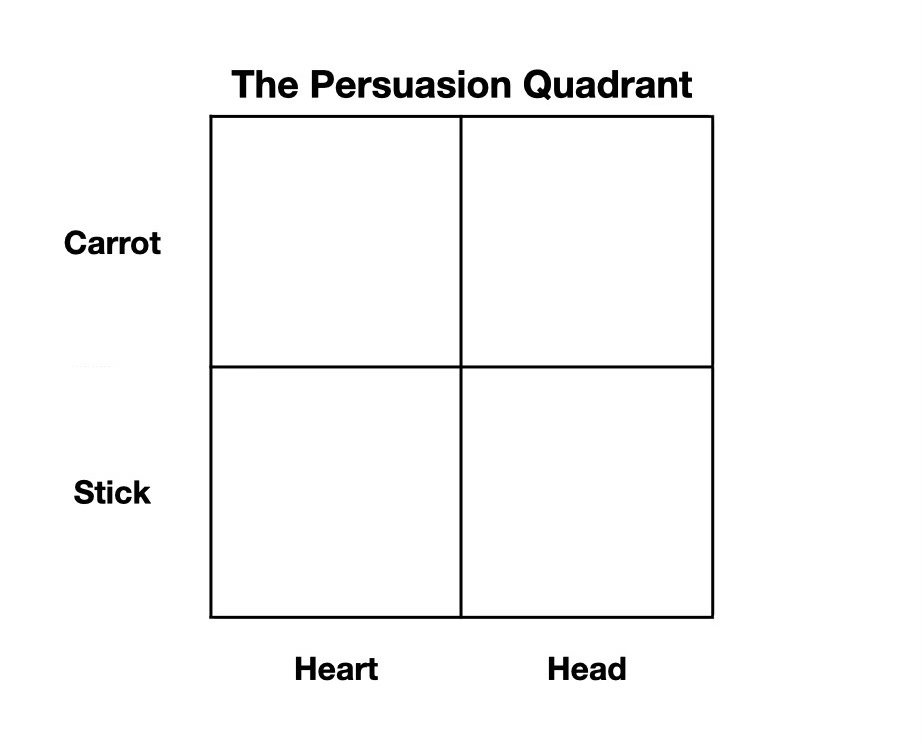

A while back, I developed the Persuasion Quadrant to help people focus their messages:

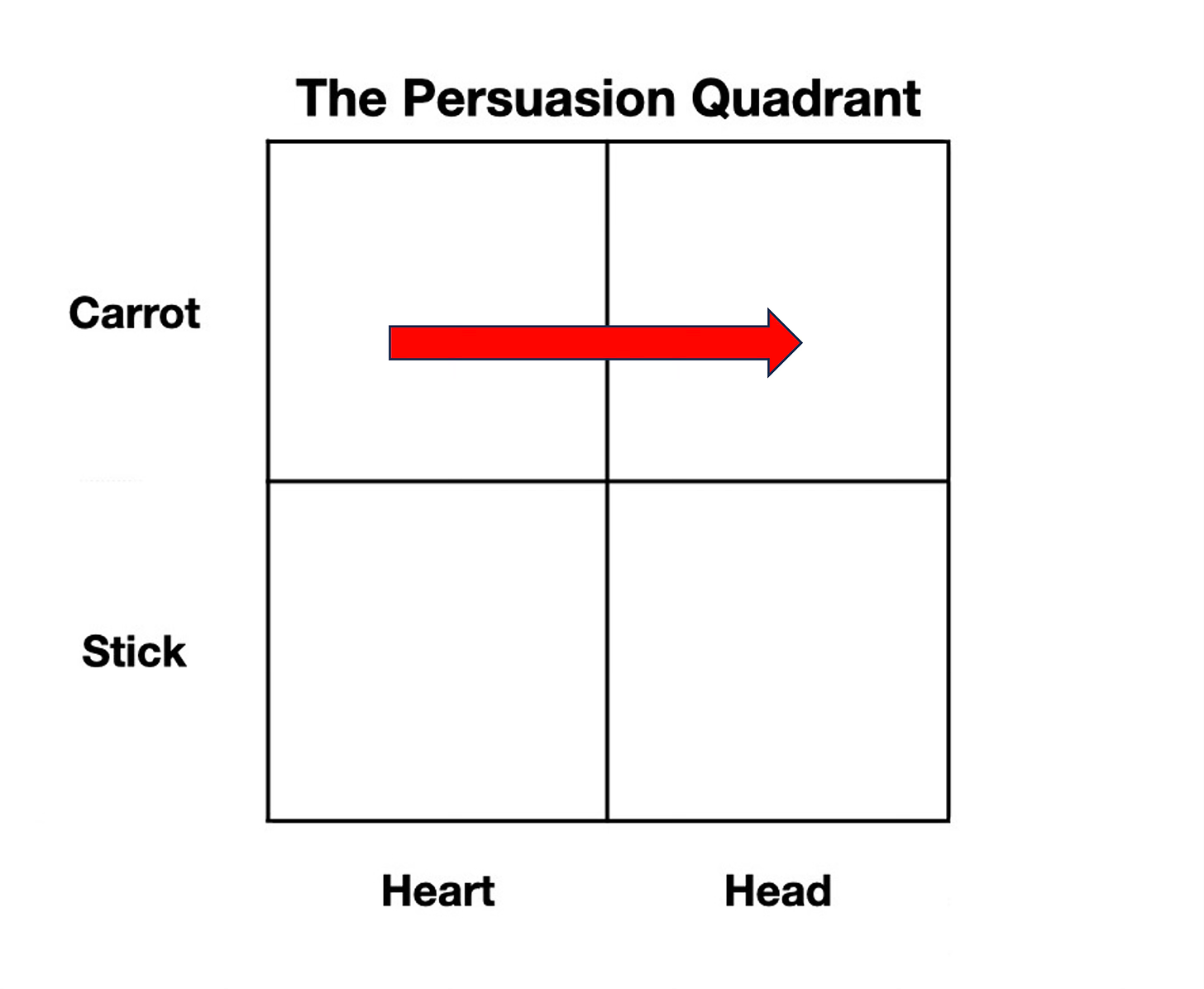

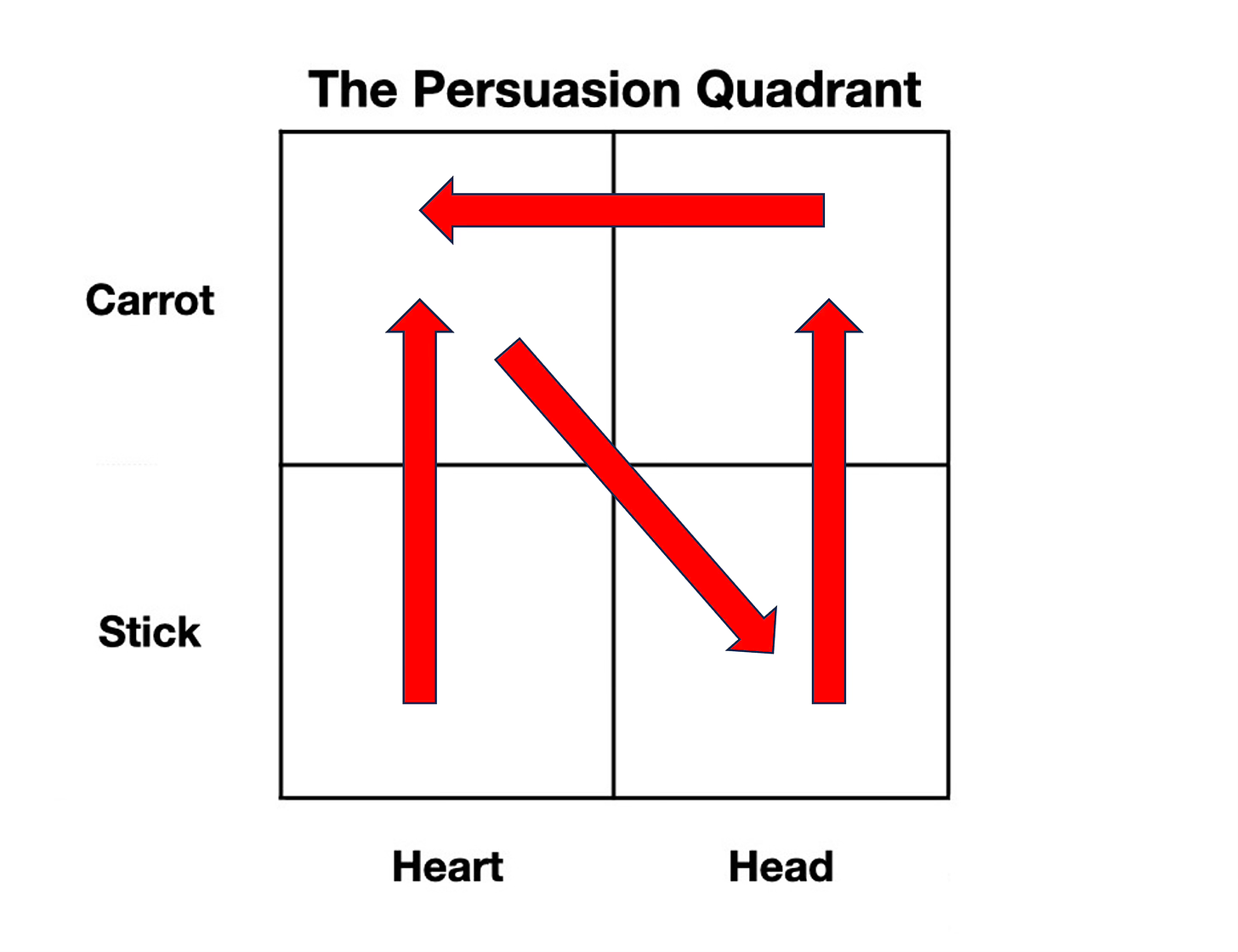

At the time I first wrote about this, I was concerned with localizing an overall message on the chart. These days, though, I’m thinking about movement across the chart. Persuasive exercises exist in time, and you can think about each exercise as a journey from one quadrant to another.

With my friend S, the journey was this:

But I can imagine other journeys from the simple to the complex like this:

The point is that every persuasive exercise—even something as simple as an email subject line—has a beginning, middle, and end, so thinking about the other person’s journey will make you more effective.

What’s in it for all parties?

One of the best lessons in persuasion I ever got came from Rick Parkhill, who was my CEO at iMedia Communications. That’s where I had my first Editor in Chief stint running content for the sadly-now-defunct daily media property, iMedia Connection.

Confession: I’m an advertising heretic. Even though I’ve worked in ad tech for years, I’m not-so-secretly invested in the value of personal privacy. I’ve donated to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, think that the legislative initiatives popping up all over the world to prevent big tech from tracking our every click are great ideas, and want Congress to remove the Section 230 protections that give online companies immunity from all the hateful, harmful, cyberbullying and misinformation that happens on their platforms.

Back in my iMedia days, I wanted to organize a panel at the 2005 Computers, Freedom, and Privacy conference where two companies selling behavioral targeting for advertising and two privacy advocates would debate.

I pitched Rick the idea, whereupon he raised his eyebrows and asked, “What’s in it for iMedia?” It was a great question. The ad tracking companies and privacy advocates would all benefit from learning more about each other, and the audience would benefit from learning about the complexities of the issue, but how would iMedia benefit?

My answer, after I thought about it for a moment, was three-fold. First, it would bond us more closely to the two behavioral targeting companies that were frequent contributors and sponsors. Second, it would present iMedia as a platform for thought leadership around these issues to a broader audience that wasn’t familiar with our work. Third, I’d get exposed to a wider conversation around these and other issues, which would make me more effective in my job.

Rick listened, shrugged, and said, “OK.” I started making plans for the conference.

His question has stuck with me ever since, and I’ve asked it of others many, many times. “What’s in this for you?” doesn’t mean that you have to approach things transactionally. Instead, it means that you need to be clear-sighted about why you’re doing something. Those reasons can be self-interested, altruistic, or both, but if you don’t know why you’re doing it, then why bother?

Sometimes, the first person you need to persuade is yourself.

Thanks for reading. See you next Sunday.

Note: If you’d like to receive articles like this one, plus a whole lot more, directly in your inbox, then please subscribe to my free weekly newsletter!

About the image: I used this prompt: “A photorealistic image of one man speaking in an intense but civil way to another man. The second man looks completely unpersuaded. They are sitting at an outdoor cafe. The weather is sunny and pleasant. At the unpersuaded man’s feet a tricolor pembroke welsh corgi sleeps peacefully.” The corgi is neither tricolor nor sleeping, but otherwise Adobe Firefly did a good job.

Leave a Reply